The Codex App Has Upended My Daily Workflow

I haven't opened my IDE in days. I'm not sure I miss it.

Disclaimer: Regular readers will know that I currently work at OpenAI. And while that certainly introduces some bias, the views presented here are entirely my own, without input from the company.

I’m unlikely to post about every new release, but I have been so enamored with the new Codex App (and I have seen firsthand how hard the team has worked to make it great) that I am genuinely excited to evangelize this thing.

Last week, I realized I hadn’t opened my AI IDE in four days.

This wasn’t a conscious decision - no dramatic uninstall, no declaration that I was done with IDEs. I just… stopped needing it. I was shipping code, reviewing PRs, and debugging issues. The work was getting done. And at some point, I noticed the IDE wasn’t part of that loop anymore.

The reason for that was the new Codex app, which launched today. I’ve been using an early build for the past few weeks, and it’s genuinely shifted how I work - not incrementally, but structurally. My job now looks less like “writing code” and more like “managing a small team of agents who write code for me.”1

What’s New in the Codex App

Back in July, I wrote about how fast the AI coding landscape is moving:

About four years ago, the first preview of GitHub Copilot launched - a tool that was marginally useful for many but had plenty of sharp corners. But we quickly blew past that. We then moved to chatbots within AI-native IDEs, where we could ask ChatGPT or Claude questions directly within our codebases… And then things changed yet again - even faster. Now, AI doesn’t just generate one-off turn-based code snippets for us to accept or reject. They generate entire swaths of code changes in sequence, search our local filesystem, run terminal commands, and even connect to MCP servers.

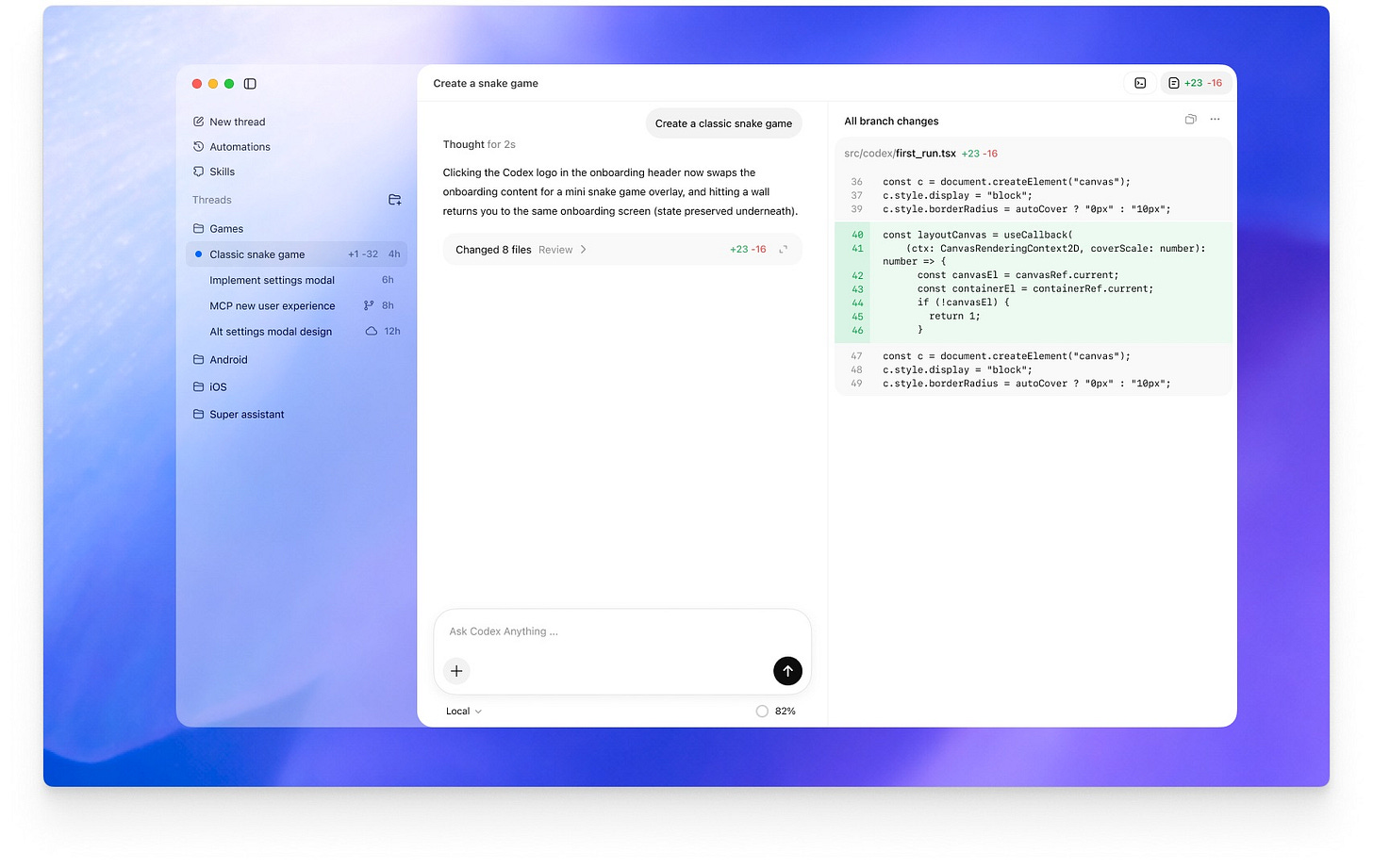

The Codex app feels like the next step in that progression. It takes the agentic capabilities pioneered by tools like Claude Code and wraps them in a proper desktop app rather than a terminal interface. That might sound like a minor upgrade, but at least for me, the difference in affordances is significant - better visibility into what the agent is doing, easier context management, and a surface area that can accommodate features a CLI or IDE simply can’t.2

The primitives that make it work:

Skills: pre-packaged instructions, prompts, and scripts the agent can discover and use on demand.

MCPs: connections to external services - Linear, GitHub, Slack - so the agent can pull context and take actions beyond just your local filesystem.

Git worktrees: native support for multiple checkouts of the same repo simultaneously, enabling genuinely parallel agent workflows.

Compaction: intelligent context pruning that lets conversations run for hours without degrading. This is what makes extended sessions viable.

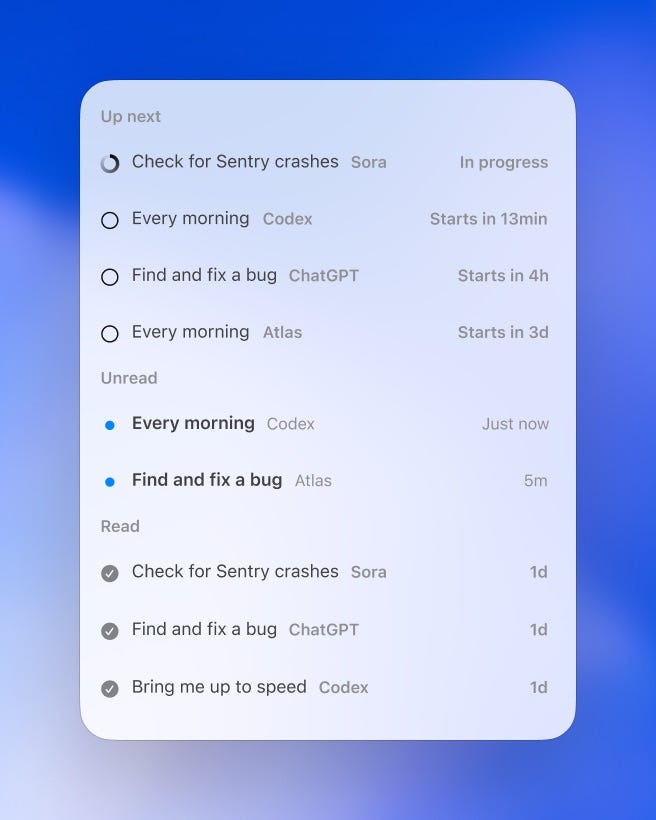

Automations: scheduled background tasks that execute on your behalf, opening up even more possibilities.

The desktop format matters because there’s only so much you can do in a terminal. You can build all of this in CLI - and many people do - but it’s clunkier. The app gives you the ability to see multiple contexts at once, manage worktrees visually, and watch what your agents are doing without parsing streaming text.

From Theory to Practice

Two weeks ago, I wrote about the shift from maker’s schedule to manager’s schedule:

I’m moving away from chatting with AIs and moving towards managing them. You can see the progression of these tools. Today, they’re primarily designed around coding, but it’s a very short leap to augment them for general-purpose knowledge work. Which means those of us at the cutting edge will shift our schedules and workflows from those of makers to those of managers.

This isn’t hypothetical anymore. It’s my actual daily workflow.

Right now, three main drivers have shaped how I get the most from the app:

Parallelization

Layering primitives

Long-running threads

There are a bunch more features in the app, like plan mode, personalities, and more - but these are the three that have most impacted me. Let’s dig into them.

Worktrees for Parallel Work

The primitive that makes “managing agents” literal rather than metaphorical: git worktrees.

This was a new concept for me, but to oversimplify: worktrees let you have multiple checkouts of the same repo open at the same time. Each one can run its own Codex session.

For example, with worktrees, you could have three sessions going in parallel: one refactoring your authentication flow, one fixing a gnarly timezone bug, and one building out a new dashboard component. Each one can make changes without fear of clobbering the other, and each one can still run the project locally to preview the changes (merging/syncing remains tricky, but the team has done some impressive work to make this a lot less of a headache than it otherwise might be).

In my own work, I end up context-switching between them as a reviewer - reading diffs, asking clarifying questions, occasionally redirecting - rather than as an implementer.

I’m still figuring out the best patterns here. The learning curve isn’t gentle. But when it clicks, it’s a genuine multiplier - not 10x productivity in some handwavy sense, but the concrete ability to have multiple meaningful workstreams advancing simultaneously.

In the Manager’s Schedule piece, I wrote about orchestration:

Of course, why stop at delegating to a single agent, or only working on one project at a time? The next level of managing AI becomes effectively orchestrating multiple lines of work, either via multiple agents or in tandem with other, non-delegated work… A new ability that I’ve been developing is keeping track of two different piles of work: work that can be automated in small chunks, like small bugfixes or coding tasks, and work that fits well when interleaved between those chunks.

Worktrees are what make this practical. Without them, parallel agent work means constantly stashing changes, switching branches, and losing context. With them, each workstream is isolated and persistent.

Skills + MCPs + Automations

The next piece is taking the core app capabilities and layering on more agentic primitives - specifically, Skills, MCPs, and Automations. I won’t go into vast amounts of detail here, mostly because I’ve already done a write-up of the first two.

Individually, each one is certainly useful. But the real leverage comes from combining them. Some examples that I’ve been playing around with (and several more from the official blog):

Every day at 9am, check my open Linear tasks, prioritize them, and create a starter prompt for each to give to a new coding thread.

Use the Playwright MCP to verify your frontend changes are actually working as you go.

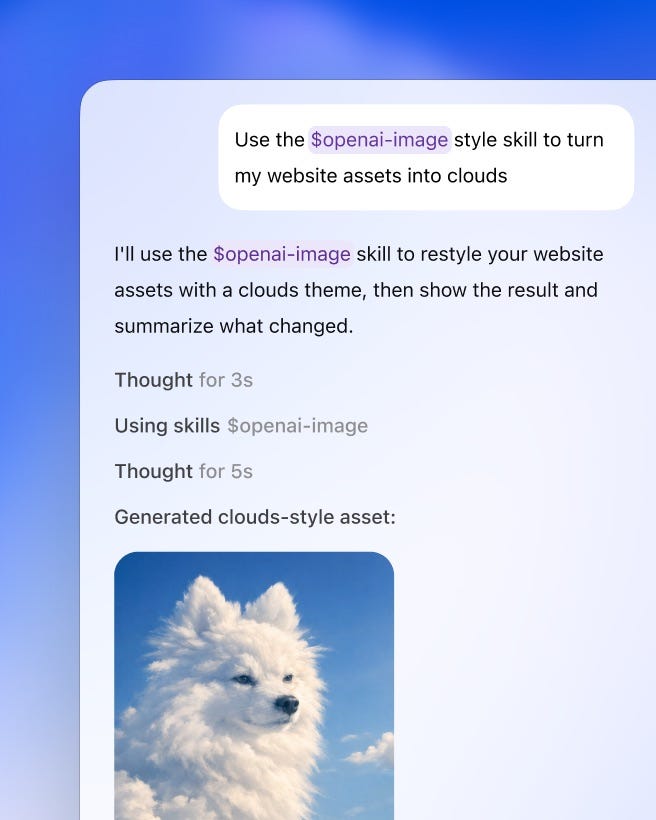

Invoke the

$reviewSkill, which checks my recent commits for possible bugs and suggests fixes.Fetch design context, assets, and screenshots from Figma and translate them into production-ready UI code with 1:1 visual parity.

Have Codex deploy my web app creations to popular cloud hosts like Cloudflare(, Netlify, Render, and Vercel.

Use the image generation skill powered by GPT Image to create and edit images to use in websites, UI mockups, product visuals, and game assets.

None of these is revolutionary on its own. But stacked together, they start to feel like infrastructure - a scaffolding that lets me operate at a higher level of abstraction than I could with just a model and a prompt. What’s fascinating is that automations also seem to be opening people’s eyes to what’s possible with agents - a similar “heartbeat” mechanism is what’s made OpenClaw/Clawdbot feel so much more impactful than previous chat-based incarnations of agents.

I’m still discovering new ways to invoke Skills, connect MCPs, and build Automations. The surface area is large, and I haven’t explored many workflows yet. With any luck, I’ll have some best better practices to share in a month or two.

Why I Stopped Starting Over

In my experience, I’m the type of person who starts a brand new thread for every little ChatGPT task I work on. Once I found out how context windows and in-context learning worked, I wanted to keep things as clean and repeatable as possible for each task.

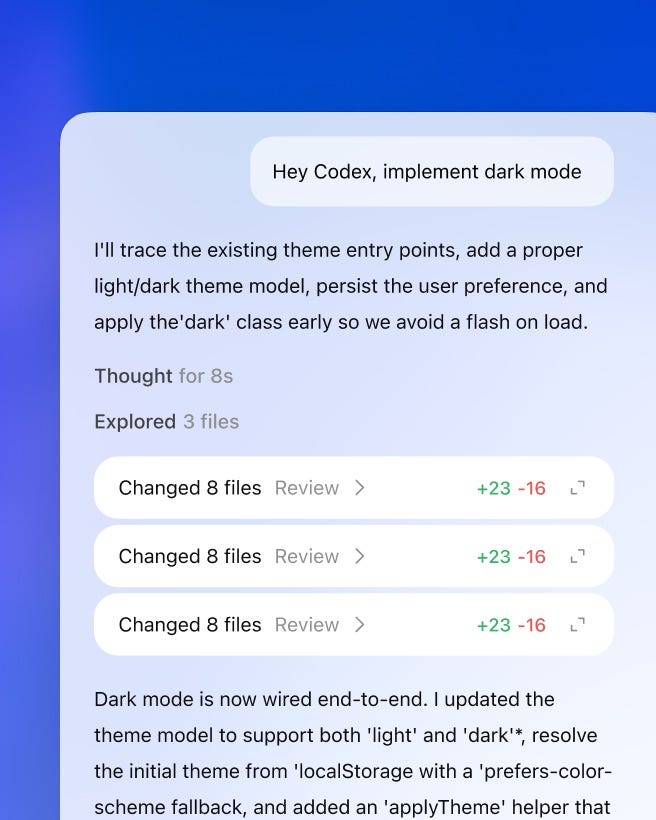

The Codex app has changed this - I now run multiple tasks and multiple turns in a long-running thread (when I’m not splitting things out via worktrees). Two things have enabled this:

First, compaction. We’ve reached the point where models can automatically and intelligently shrink their conversation history. However the labs are doing this, it’s gotten quite good. As I work, the model builds context about my codebase, preferences, and patterns. I’m not constantly re-explaining things, which is nice.3

Second, better models. The current narrative is that Claude Code is the best agentic coding tool, but I’ve been finding real success with GPT-5.2-Codex, particularly for the kind of parallel, delegated workflows I described above. It’s also changed how I think about prompting and planning - I’m spending more time creating detailed PLAN.md files, knowing that Codex can go off and (usually) get the entire thing working.

Codex can be slower than Claude, but when you’re managing multiple worktrees rather than iterating quickly in a tight CLI loop, speed matters less than thoroughness. I’d rather have an agent that takes twenty minutes and gets it right than one that takes five minutes and needs three rounds of correction.

And it would appear I’m not alone - Cursor itself has been referring to Codex as the best model for extended, autonomous work:

Model choice matters for extremely long-running tasks. We found that GPT-5.2 models are much better at extended autonomous work: following instructions, keeping focus, avoiding drift, and implementing things precisely and completely.

Opus 4.5 tends to stop earlier and take shortcuts when convenient, yielding back control quickly. We also found that different models excel at different roles. GPT-5.2 is a better planner than GPT-5.1-Codex, even though the latter is trained specifically for coding. We now use the model best suited for each role rather than one universal model.

This combination - compaction plus models trained for long-horizon work - means conversations that would have degraded into nonsense six months ago now stay coherent across hours of work. It’s more like working with a colleague who remembers yesterday than briefing a stranger from scratch each time.

The Bittersweet Question

All of this has been practically useful. But it’s also been slightly bittersweet.

I routinely think about Kent Beck’s observation that 90% of his skills are now worth $0, while the remaining 10% went up 1000x in leverage. That’s more true now than when I first quoted it last year.

There are two types of programmers: those who care primarily about the output - the website, the app, the shipped feature - and those who love the craft of building itself. For the former group, AI coding tools are pure upside. For the latter, something is being lost.

I’m in the latter camp. I’ve loved programming since I first learned to program. There’s something deeply satisfying about crafting something from scratch, about the frustrating-fun of debugging, about the elegance of a well-designed system.4 And I’m learning to let go of some of that - learning to let go of every line of code being written.5

But I’ve also realized that my relationship to craft has changed as I’ve matured as a programmer. I’m approaching middle age now, in a different season of life than when I was writing code at 2am for the pure joy of it.

My hope is that the craft has shifted, not disappeared. Indeed, the meta-skills I use now are different from the ones I spent a decade honing. Vision, taste, judgment, the ability to see what should exist and guide it into being. Those are the 10% that matter more than ever.

I previously used the analogy of software as akin to carpentry:

If I’m working with an advanced carpenter to help me design something, I don’t particularly care if they’re the one doing the actual sawing and gluing. I’m working with them for the final product, not the specific mechanical steps.

I’m becoming that carpenter. The sawing and gluing are increasingly delegated. What remains is the part that was always the hardest: knowing what to build, and whether it’s any good.

For anyone who’s loved CLI coding tools but found them clunky, Codex is worth trying. For anyone skeptical of agentic coding, this might be the version that changes your mind.

Of course, I’ll be the first to admit that this level of changeover is somewhat project-dependent. If you’re working in a tightly constrained environment, the CLI/IDE tools might still be the better fit. But for my workflow - lots of frontend, multiple repos, frequent context-switching - the app format is meaningfully better.

It also automatically benefits from the features of Codex in general - cloud tasks, steerability, and general model improvements.

Though you should definitely be using AGENTS.md for things you need to bake into your preferences at the project level!

Anecdotally, this might be why so many programmers retire into woodworking. Same satisfaction, different material.

I still dip into the filesystem when I need to deeply internalize how something works - complex debugging sessions, understanding unfamiliar code, architectural decisions that require seeing the whole picture. But for the majority of my coding work, I’m operating at a higher level of abstraction: defining tasks, reviewing outputs, asking questions, approving changes.

Very interesting! I've been using Cursor for a while for my side project, but you inspired me to hook up my OpenAI API and test it!

Damnit, I just switched to Claude Code from Codex not two months ago, and now I'm going to have to find time to try this. For my purposes (and for context I am a not developer but a former PM using LLMs to build internal tools for my business), SOTA models all seem to be past the threshold of coding skill necessary, and now the harnesses are becoming the more important differentiating factor. Glad to see some healthy competition there, and specifically glad to see you've got automations in there, as I've specifically felt the lack of those in CC.