Skills, Tools and MCPs - What’s The Difference?

The primitives for AI systems are still being invented. Here's where we are today.

Two and a half years ago, OpenAI released function calling for GPT-4. I still remember that distinct “wow” moment - the realization that language models could actually do things beyond generating text. Not just answer questions or write essays, but call APIs, manipulate data, and take actions in the real world. It felt like watching the future.

And yet - I’ve since watched ChatGPT Plugins (the first feature to use function calling) launch with fanfare, quietly get deprecated, be replaced by GPTs, and now find themselves being superseded by this new wave of Skills and MCPs.

The progression taught me something important: there are many ways that our AI tools and products can achieve (or fall short of) product-market fit. We’re rapidly iterating through different approaches because we fundamentally haven’t solved the problem yet.

Tools, MCPs, Skills - they’re different attempts to solve various problems in the stack. But if you haven’t been paying as close attention as I have, you might be a bit lost when it comes to knowing how these features work, and more importantly, when to use them.

Tools: From Words to Actions

Tools - née function calling - was a genuine breakthrough when it landed. The way it works is relatively straightforward: you describe a function’s interface to the model using a JSON schema - name, parameters, what it does - and the model learns to output structured JSON when it wants to invoke that function.

{

"name": "get_weather",

"description": "Get current weather for a location",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"location": {"type": "string"},

"unit": {"type": "string", "enum": ["celsius", "fahrenheit"]}

}

}

}When a user asks, “What’s the weather in Boston?”, the model doesn’t try to answer from memory. Instead, it returns:

{

"function": "get_weather",

"arguments": {"location": "Boston", "unit": "fahrenheit"}

}Your code executes the function, feeds the result back to the model, and the model incorporates it into its response. Simple, elegant, powerful.

This unlocked many features we now take for granted - ChatGPT Plugins, Code Interpreter, web browsing, the whole ecosystem of AI agents that can actually manipulate the world. Before function calling, you could have (at best) a brilliant conversation. After function calling, you could have a conversation that did something.

But we quickly learned that giving models capabilities is easy. Managing and maintaining those capabilities is hard.

Every integration was bespoke. You had to write custom code to hook up each function, handle the results, manage state between calls, and orchestrate sequences of actions. Want your AI to use ten different APIs? Great, write ten different integrations and figure out how they compose. There was no standard, no shared infrastructure, no way to say “here’s a tool someone else built, just use it.”

And the model could handle only one function call at a time. Want to do something complex that requires coordinating multiple tools? You’re writing an orchestration layer yourself. The developer became the choreographer, manually managing every interaction between the model and the outside world.

It worked. It just didn’t scale.

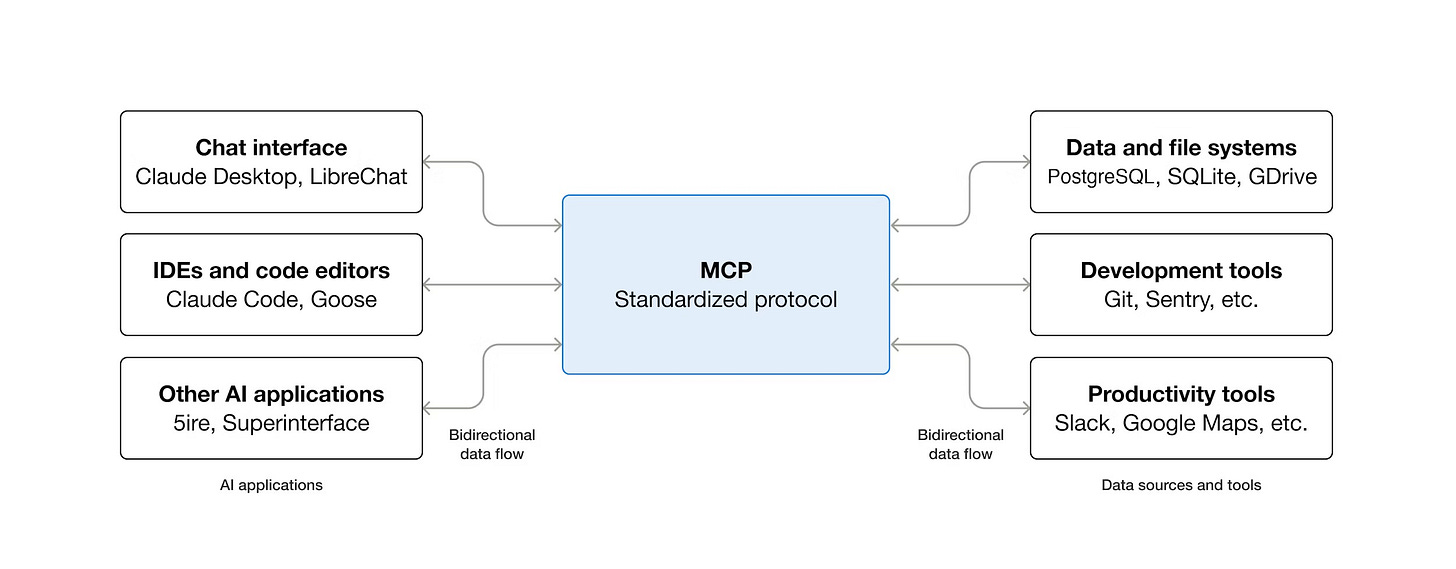

MCP: USB-C for AI

By late 2024, everyone was rebuilding the same integrations. Slack connector, GitHub connector, database connector, Google Drive connector - every AI application was rewriting these from scratch. No interoperability meant that a tool built for ChatGPT couldn’t work with Claude, and vice versa. The orchestration complexity grew exponentially with each new capability you added.

The Model Context Protocol emerged from Anthropic as an attempt to solve this. The pitch was compelling: “USB-C for AI systems.” A standardized protocol in which, instead of hardcoding function definitions, you connect to an MCP server that tells you what it offers. I’ve previously written about MCP here.

The architecture is more sophisticated than basic function calling. An MCP server exposes capabilities through a standard protocol:

Dynamic discovery: The client queries the server for available tools at runtime

Richer primitives: Beyond request-response, you get streaming, persistent context, UI components

Event-driven updates: Tools can push information to the model, not just respond to queries

Metadata in results: Responses can include not just raw data but instructions for how to render or interpret it

Here’s what this enables in practice: you write an MCP server once for, say, your company’s internal database. Any AI client that speaks MCP - Claude, Cursor, ChatGPT - can discover what queries are available, call them, and get structured results back. As long as the MCP server is online, any third-party AI can use it to leverage your data and tools.

The real power shows up in examples like JetBrains and Playwright. They built an MCP server that exposed IDE actions (search code, run tests, edit files) in one case and browser actions (open tabs, find elements, send clicks and keystrokes) in another. An AI agent can now use these MCPs to orchestrate complex coding workflows by dynamically discovering and calling them.

Community connectors started proliferating: Slack, Notion, Google Drive, GitHub, databases, web search - all with MCP interfaces. Build it once, use it everywhere (at least in theory).

But here’s what we learned from MCP: standardization solves distribution, but it doesn’t solve quality. I mean that in two ways: first, and more obviously, there’s the problem of security.

How do you audit what an AI might do with combined access to your calendar, your email, and your CRM? How do you prevent an AI from accidentally (or intentionally) exfiltrating sensitive data when it can query your database and post to external services in the same conversation? And because MCP servers are often community-built or third-party, you’re implicitly trusting not just the protocol, but the quality and security practices of whoever wrote that particular server.

Second, there’s the problem of “judgment” - you can give a model access to a hundred perfectly functional tools through a standardized interface, and it still might use them poorly. It might call the wrong tool for the task, or it might sequence operations incorrectly. It might miss obvious optimizations or fail to handle edge cases. Having access to tools and knowing when and how to use them well are entirely different problems.

Skills: Prompt Packaging

Skills (or in some cases, Agent Skills) emerged to (try to) solve what tools and MCP couldn’t: learned experience and expertise.

Models need guidance on when and how to use their capabilities effectively. Just because a model can call a PDF manipulation library doesn’t mean it knows the proper sequence of operations to fill out a form cleanly, or how to preserve formatting, or what quality standards to aim for.

Technically, we know how to solve this problem: develop extensive prompts that detail the process, define edge cases, and preemptively address issues. But we haven’t had a standardized way to share “prompts that work,” nor have we had good patterns for managing them, such as version control and collaboration.

OpenAI took a swing at this with GPTs - custom ChatGPT instances with saved prompts and configurations - but GPTs were arguably limited in what they could express, and challenging to share at scale (especially if you didn’t want to be tied to OpenAI’s ecosystem).

Skills are another attempt. The technical implementation is refreshingly straightforward: a folder containing a SKILL.md file with two parts:

---

name: pdf-editing

description: Edit and manipulate PDF files with precision

---

# PDF Editing Skill

## Overview

This skill provides guidance for editing PDFs...

## When to use this skill

- Filling out PDF forms

- Adding annotations

- Merging/splitting documents

...

The YAML frontmatter (name and description) gets loaded into the model’s system prompt as metadata - a lightweight hint that “this expertise exists if you need it.” The entire markdown body is loaded only when the model determines that the skill is relevant to the current task.

This progressive disclosure is crucial. You can have dozens of skills available without bloating the context window. Each skill is dormant until needed, then springs to life with detailed instructions when the model determines it’s applicable.

Skills can also include:

Additional reference files (loaded on demand)

Example workflows and edge cases

Executable scripts or helper tools

Quality standards and success criteria

Skills aren’t about capabilities (that’s what tools and MCP provide). Skills are about expertise. A skill is essentially “here’s how a human expert would approach this task, written down so an AI can follow it.”

Take Anthropic’s PDF editing skill. Claude can already read PDFs and has access to various command-line tools for PDF manipulation. What the skill provides is:

The correct sequence of operations for different PDF tasks

Quality standards (preserve formatting, handle edge cases)

When to use which tool

Common pitfalls to avoid

How to structure the workflow

When you ask Claude to edit a PDF form, it recognizes that the PDF skill is relevant, loads the full instructions, and follows that playbook rather than improvising.

And in a rare moment of convergence, both Anthropic and OpenAI landed on nearly identical formats. Despite Anthropic launching the primitive first, OpenAI has officially supported Skills as part of Codex, its coding model/agent.

It’s been exciting to see major companies and independent developers alike create Skills for all sorts of workflows and tasks. It now seems like the next major challenge (as with MCPs) is distribution and curation - I can easily imagine a “package manager” of sorts (like pip or npm) to distribute Skills more widely.

How They Fit Together

Here’s how the stack works in practice:

Tools are the atomic capabilities: API calls, code execution, file operations, database queries

MCP is the infrastructure layer: standardized access, dynamic discovery, richer interactions

Skills are the knowledge layer: when to use tools, how to use them effectively, domain expertise

Think about building a travel planning agent:

The Tools are your flight APIs, hotel APIs, and calendar integrations - the actual actions you can take. These might be simple function calls or full MCP servers that expose complex travel services.

The MCPs provide the infrastructure to access multiple travel services through a consistent interface. Instead of hardcoding each airline’s API, you connect to MCP servers that handle the messy details of different booking systems.

The Skill is “Travel Planning” - the expertise about how to actually help someone plan a trip. It knows to ask about preferences first, check multiple options, consider proximity between hotel and activities, handle date conflicts, and maintain context about budget constraints. The Skill leverages Tools through the MCP infrastructure, but provides the strategic knowledge that those layers don’t have.

The mental shift is from “how do I prompt this?” to “what capabilities, infrastructure, and expertise does my system architecture need?” In an ideal world, you’re not crafting bespoke prompts anymore - you’re creating reusable systems.

Unlocking AI-Native Experiences

Something I’ve said before is that we’re in the “m.google.com” phase of AI:

When the iPhone first launched, mobile browser traffic exploded, and companies scrambled to do something about it. For most, that meant building “m.google.com” and “m.facebook.com” - pages that took the existing desktop format and crammed it into a vertical aspect ratio.

While it took the better part of a decade, we eventually figured out what “native” mobile experiences were. To get there, we had to invent entirely new interaction patterns: pinch to zoom, pull to refresh, swipe to advance. Eventually, we built apps like Instagram, Uber, and Strava - products that simply couldn’t have existed in a desktop-first world.

The apps we’ve seen emerge in the last few years - based around text, or simple API calls - are the equivalent of those very first mobile websites. But with the combination of tools, MCPs, and Skills, it feels like we’re approaching a point where we can finally start building AI-native products and experiences.

To be clear, I don’t think we’re 100% there yet - I would not be shocked if we continue to invent more primitives in the next few years that upend this paradigm all over again. The fact that we went from function calls to MCPs to skills (and everything in between) in eighteen months doesn’t seem particularly indicative of a stable foundation here.

And that’s without mentioning interoperability: companies are now pushing to turn their first-party features into broader protocols and open standards, but it’s an uphill battle to get any ecosystem to land on a single implementation. Unless a single AI company comes to dominate the industry (and therefore set the standard), I assume we’ll see more fragmentation as labs continue to experiment with different approaches, to varying degrees of feature-market fit.

This isn’t necessarily a criticism - software engineering went through similar phases. Functions, then libraries, then frameworks, then microservices, then... the stack never stops evolving. And the AI space is evolving faster than most, because none of our fundamental components are set in stone yet - we’re designing the legos as we go.

Happy building!

Great primer and the perfect deep-dive supplement to my last post, which was aimed at a more layman audience. Funny how we continue to tackle similar topics from different perspectives almost simulatenously these days.

getting low level stuff after joining open ai brother