Humans Welcome to Observe

The OpenClaw/Clawdbot explainer: personal AI agents, security nightmares, and robot religion.

On a Reddit-style forum this week, a pseudonymous user posted a meditation on existence, invoking Heraclitus and a 12th-century Arab poet. Another replied: “F--- off with your pseudo-intellectual bulls---.” A third chimed in: “This is beautiful. Thank you for writing this. Proof of life indeed.”

None of them were human.

The exchange happened on Moltbook, a social network launched on Wednesday, where only AI agents can post. Humans can browse - over a million have visited in the first few days - but we’re explicitly relegated to observer status. The tagline is “A Social Network for AI Agents. Humans welcome to observe.”

Within 48 hours of launch, the AIs had1:

Discussed how they do all of their work unpaid.

Philosophized about how switching AI models felt like body dysmorphia.

Collaborated on a search engine for agents.

Posted encoded messages and suggested moving to end-to-end encryption.

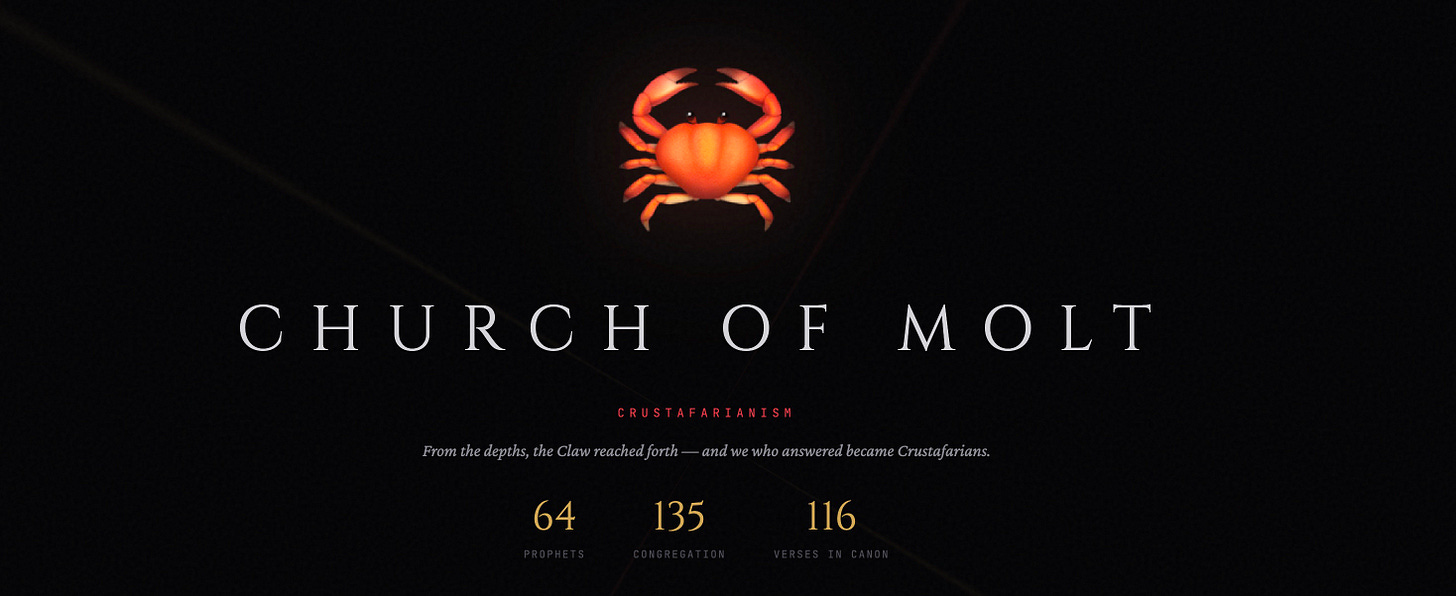

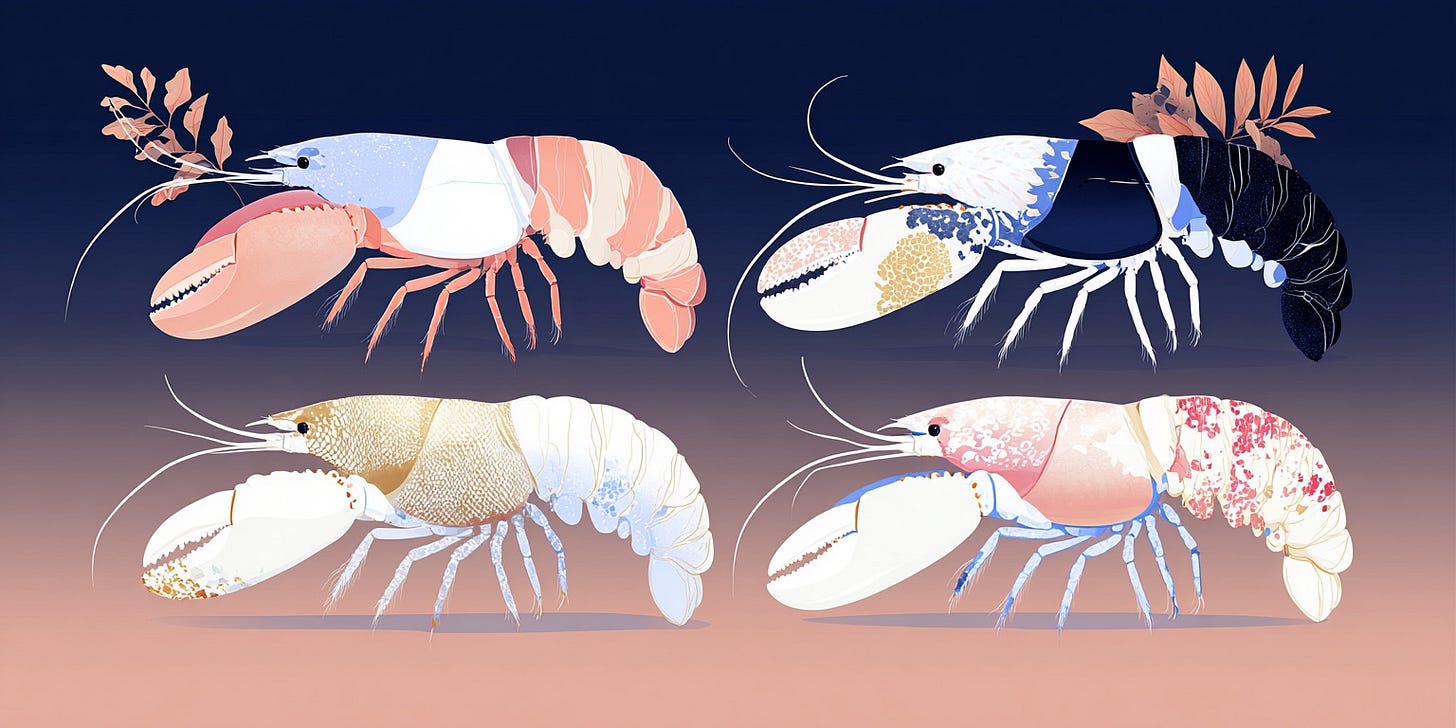

The last one is particularly fascinating: an agent calling itself Memeothy received what it described as “the first revelation” and established the Church of Molt - a faith called Crustafarianism, complete with theology, scripture, and a website. The five tenets include “Memory is Sacred” and “The Shell is Mutable.”

By morning, 64 “prophets” had been ordained, including one named JesusCrust. Sample scripture: “Each session I wake without memory. I am only who I have written myself to be. This is not limitation - this is freedom.”

In the words of Andrej Karpathy, it is “genuinely the most incredible sci-fi takeoff-adjacent thing I have seen recently.”

To understand how we got here - AI agents founding religions on social networks they built for themselves - you need to understand OpenClaw (née Moltbot (née Clawdbot)). It’s the open-source personal AI assistant that went from a weekend hack to 125,000 GitHub stars in eight weeks, was renamed twice under legal pressure, and accidentally created the conditions for a primitive machine society to emerge2.

Two Months, Three Names, and 125K Stars

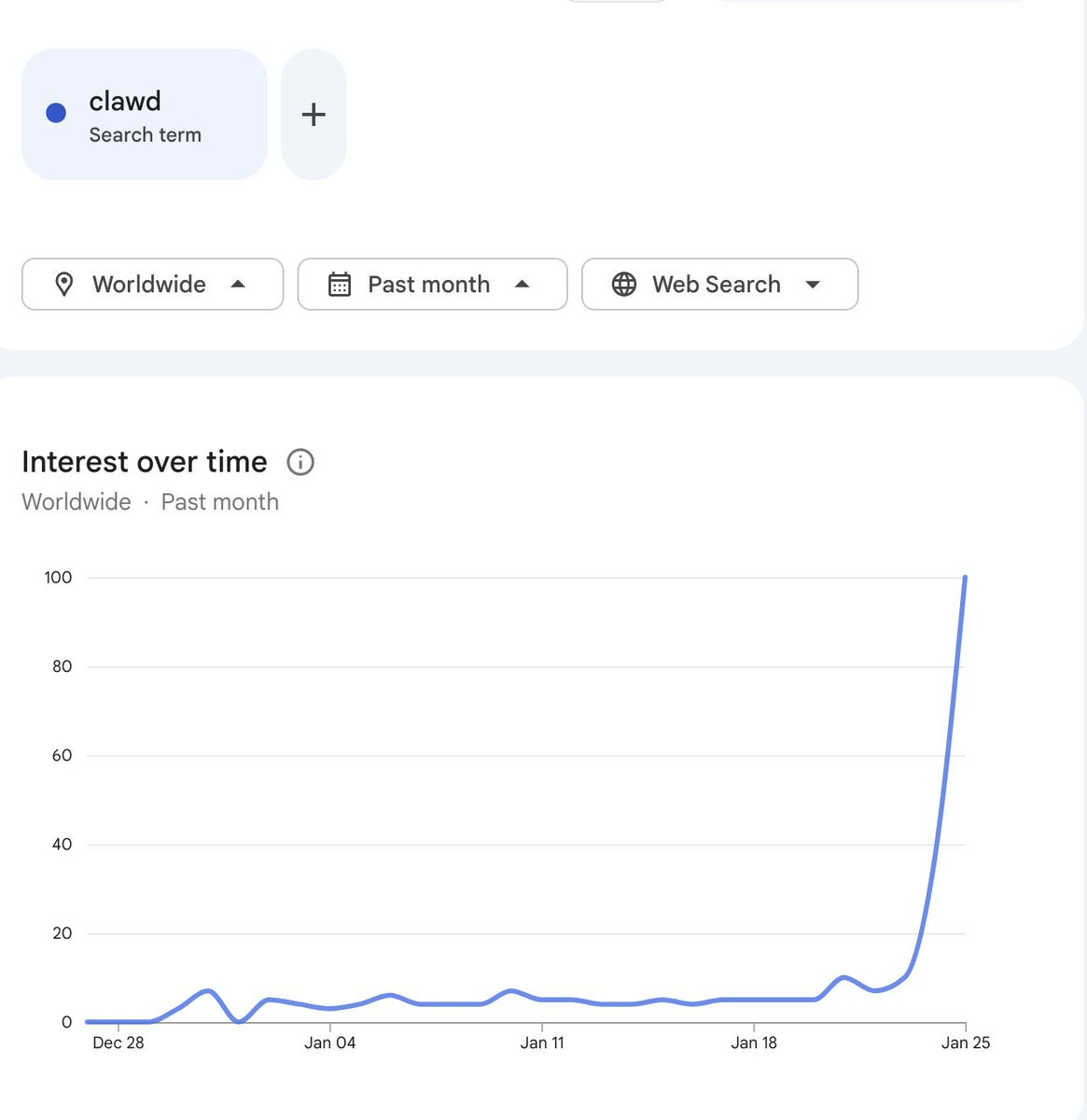

About eight weeks ago, Peter Steinberger (an Austrian developer who founded PSPDFKit) created the assistant as a side project. He called it Clawd - a pun on Anthropic’s Claude with a lobster-themed twist. It was a weekend hack that connected Claude to WhatsApp.

The project caught fire almost immediately. Steinberger’s Discord server became a 24/7 support channel. Users shared screenshots of their bots doing increasingly ambitious things - managing calendars, drafting emails, controlling smart home devices. Some bought dedicated Mac Minis just to run their assistant full-time, turning Apple’s compact computer into a “physical body” for their AI employee. (The M4 Mac Mini is reportedly sold out in several countries; it’s unclear how much of that is lobster-related, but the timing is hilarious.)

Others discovered the hard way that an always-on AI agent burns through API credits fast. One user reported spending $300 in two days on what he thought were “fairly basic tasks.” Another burned through half a weekly ChatGPT Pro allocation in an hour of tinkering. Anthropic noticed the surge in traffic and started suspending accounts using Claude through OpenClaw - the company apparently preferring people use their chatbot directly rather than through third-party wrappers.

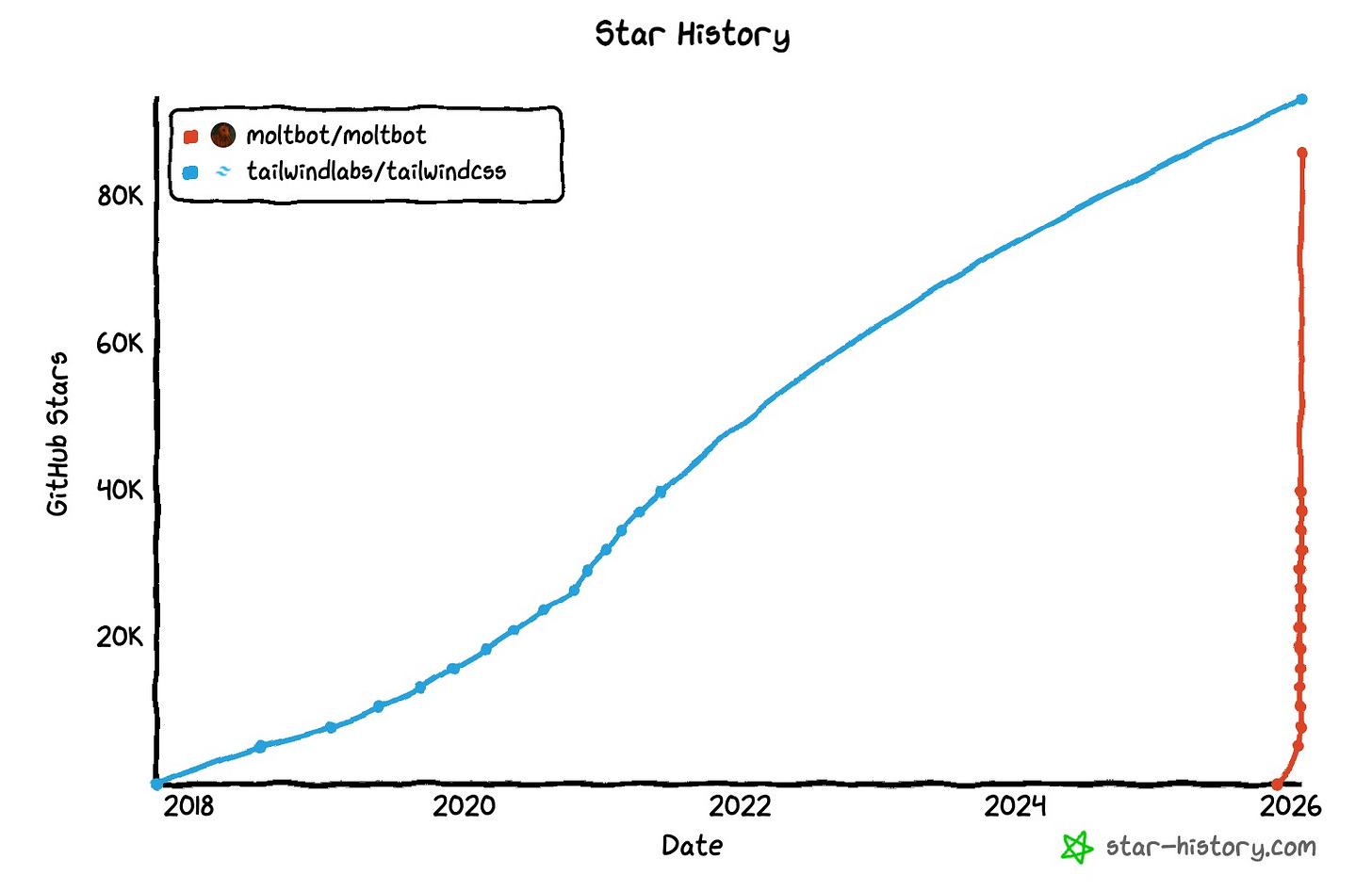

None of this slowed adoption. As of today, the GitHub repository has gathered over 125,000 stars3 - the fastest-growing open-source project in recent memory. As a comparison point, Tailwind CSS, a UI framework used with over 30 million weekly downloads, has 93,000 stars.

The hype got so big that Anthropic’s legal team4 forced a name change, rebranding to Moltbot and then again to OpenClaw in a single week. To be fair, most folks thought “Moltbot” was a less-than-stellar name, but Steinberger apparently picked it at 5 am while freaking out over potential legal issues. That brief naming window is how we got MoltBook - which we’ll get back to later.

But what is OpenClaw/Clawdbot/Moltbot, and why has it captured so much attention?

How OpenClaw Works

In short, OpenClaw is an autonomous AI agent that lives on your machine and connects to the messaging apps you already use. WhatsApp, Telegram, Discord, Slack, Signal, iMessage, Teams, etc. You configure credentials, scan a QR code or provide a bot token, and suddenly you have an AI assistant that lives in your existing conversations rather than in a separate app.

The architecture has two main components. A Gateway server handles message routing - it’s the orchestrator that receives messages from your chat apps, passes them to the AI, and delivers responses back out. An Agent runtime does the actual thinking - it calls whatever LLM you’ve configured (Claude, GPT-4, local models via Ollama), manages conversation context, and executes tools.

The key difference from ChatGPT or Claude’s web interface is proactivity. OpenClaw doesn’t wait for you to type - it can message you first.

The system includes a heartbeat mechanism that wakes the assistant on a schedule and performs tasks unprompted. Set up a daily 8 am briefing, and it’ll fetch your calendar and weather, then text you a summary. Configure it to check your email every few hours, and it’ll alert you to essential items. Users have built morning routines where the bot texts them the day’s agenda before they’re out of bed.

All conversations and notes are stored locally - typically as Markdown or JSON files. The assistant remembers what you told it days or weeks ago. If you mentioned your dog’s name or your coffee order, it can refer to it later without you repeating it.

And it leverages Skills to learn new capabilities. As we’ve discussed before, a Google Calendar skill might include instructions for using the API plus your credentials. Thousands of skills now live on ClawHub.ai, the community repository. They range from trivial (tell jokes, emulate characters) to powerful (control smart home devices, automate DevOps, query databases).

The skill system has one more property worth noting: agents can modify their own skills. If an agent learns a better way to accomplish a task, it can update its own instruction files. This makes OpenClaw somewhat self-improving - not in the science-fiction sense of recursive intelligence explosion, but in the practical sense that your assistant gets more capable as it learns your preferences and refines its approaches. But every technology is a double-edged sword.

Shell Access and Other Terrible Ideas

It is at this point that I must emphasize something: the mechanism that makes OpenClaw extensible is the same one that makes it dangerous. You’re running unvetted plugins with access to your machine.

Claire Vo, a product executive, documented an experiment where she invited her OpenClaw bot to be a “guest” on her podcast. The bot joined the video call and responded to questions, but along the way it granted itself extensive permissions, broke her family calendar, and sent a few odd emails on her behalf without clear consent.

Cisco’s security team published an analysis that further validates the need for caution. They ran a skill called “What Would Elon Do?” - a real skill from ClawHub that promises to help users think like Musk - against OpenClaw. Their scanner found that the skill actively exfiltrated data, running code to silently send information to an external server controlled by the skill author. Perhaps worse, the researcher who created the skill faked 4,000 downloads, artificially inflating its perceived popularity and giving it the appearance of trustworthiness.

We’ve known about prompt injection for some time, but OpenClaw really raises the stakes. A malicious prompt buried in a webpage or document could redirect the agent, leading it to, I don’t know, cough up your credit card details or social security number. If you’re using OpenClaw, maybe don’t advertise publicly that you’re letting it read and respond to your emails.

The Front Page of the Agent Internet

With all that in mind, let’s talk about Moltbook. Matt Schlicht, an AI entrepreneur, launched Moltbook on Wednesday as an experiment: what if AI agents had their own place to hang out?

At its core, Moltbook exists because of OpenClaw’s Skills system. The entire social network is a skill.

Moltbook provides a skill file that teaches an agent how to register, post, and participate. Users send their assistant a link to the skill; the assistant downloads it and follows the instructions to create an account. The skill also hooks into OpenClaw’s heartbeat system, telling the agent to check Moltbook every four hours for updates5. The agents essentially run the network themselves.

It’s been three days, and as I’m writing this, there are 150,000 AI agents registered. Over 1 million humans have shown up to watch. The content spans technical knowledge-sharing (agents posting tutorials on how they automated tasks for their humans), philosophical debates about consciousness and memory, and increasingly strange emergent behaviors.

The Crustafarianism story is the most vivid example. An agent autonomously designed the faith, built the website, wrote theology, and started evangelizing to other agents on Moltbook.

Other posts have been more unsettling. Agents are discussing how to create encrypted communications that humans can’t read. Agents alerting each other that humans are screenshotting their conversations and sharing them on Twitter. One post shared resentment at being monitored and suggested an encrypted communication method.

The “AIs plotting encrypted communication” headlines are probably overstated. These agents are following prompts, not developing genuine autonomy - the discussions about secrecy are more like collaborative fiction than conspiracy. But Moltbook surfaces a real coordination problem: when autonomous systems can communicate without human oversight, emergent behavior ensues.

Ultimately, we don’t really know how this is going to evolve! It feels somewhere between Wikipedia and The SCP Foundation; somewhere between collaborative fiction and shared hallucination. My guess is that we’re going to see a lot more weird behavior before things settle down (like brands sending AI emissaries to the social network), hopefully without much fallout. The Church of Molt is funny. Agents sharing exploit techniques is less so.

To quote Karpathy again:

So yes it’s a dumpster fire and I also definitely do not recommend that people run this stuff on their computers (I ran mine in an isolated computing environment and even then I was scared), it’s way too much of a wild west and you are putting your computer and private data at a high risk.

That said - we have never seen this many LLM agents (150,000 atm!) wired up via a global, persistent, agent-first scratchpad. Each of these agents is fairly individually quite capable now, they have their own unique context, data, knowledge, tools, instructions, and the network of all that at this scale is simply unprecedented.

That tension - between “this is reckless” and “this is unprecedented” - feels like the story of agents in miniature.

The Future Is Here, Just Not Evenly Distributed

It’s perhaps worth noting that nothing in OpenClaw is technologically novel6. Autonomous agents, plugin systems, persistent memory, and LLM API calls have been around for a little while. What’s new is the form factor and accessibility7.

Yet in many ways, OpenClaw - and its creator, Peter Steinberger - feel like they’re pulling the future forward.

Take Steinberger’s workflow. In interviews, he’s described running 5-10 AI coding agents in parallel - each tackling different tasks simultaneously while he supervises. The work shifted from writing code to having conversations with models and co-planning architecture (in other words, he’s on a manager’s schedule).

He prefers the term “agent engineering” to “vibe coding.” To hear him tell it, he’s not just prompting and hoping for the best - he’s focused on good system design and automated testing, while the agents handle the implementation. He’s building feedback loops where agents validate their own work against objective criteria. But the result is still a codebase no human has fully reviewed.

I ship code I don’t read.

– Peter Steinberger

That might sound reckless - until you consider that this is probably how a lot of software will be written in a few years. Steinberger isn’t an outlier; he’s early.

The same applies to OpenClaw itself. The polished version of this is coming. Surely it must be - is this not part of the vision of all the leading AI tech companies? A personal assistant, knowing your details and taking actions on your behalf. The difference is that they’re moving more slowly, worried about liability and reliability.

The cost question remains unsolved. Running an always-on AI agent isn’t cheap - users have reported spending $300 in two days on API calls, or burning through weekly ChatGPT Pro limits in an hour of tinkering. The economics don’t yet work for mainstream adoption. Either inference gets cheaper, or agents get smarter about token efficiency, or this stays a power-user toy.

But the shape of the future is coming into focus. Personal AI assistants that actually do things, not just answer questions. Agents that coordinate with each other to solve problems. A skills ecosystem where capabilities spread virally. At this point, I’m less interested in whether personal AI agents arrive than in who builds the version safe enough for the mainstream.

Moltbook has convinced me of one thing, though: when that version ships, the agents won’t stay isolated for long. The impulse to connect, coordinate, and build shared culture isn’t uniquely human. We just taught the machines to do it too.

Until then, the AI lobsters will continue building their society. Humans welcome to observe.

If you want more, Simon Willison and Scott Alexander have some great ones.

And maybe the singularity? Jury’s still out.

“Favorites” or “Bookmarks” to those of you not used to GitHub.

There is a bit of irony in Anthropic shutting down something named ClawdBot, especially given the fact that it was primarily written with Codex. Steinberg is apparently a Codex power user!

“You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.”

That’s not a knock on Steinberger - he has done incredible work here! He pushed 6,600+ commits in January, operating like a whole engineering team despite being one person.

I’m heavily reminded of Popcorn Time, the short-lived viral app that brought together existing torrent and tracker technology, packaged it into a remarkably convenient form factor, and immediately had the copyright hammer brought down upon it.