Anthropic Might Legally Owe Me Thousands of Dollars

On shadow libraries, legal documents, and judicial skepticism.

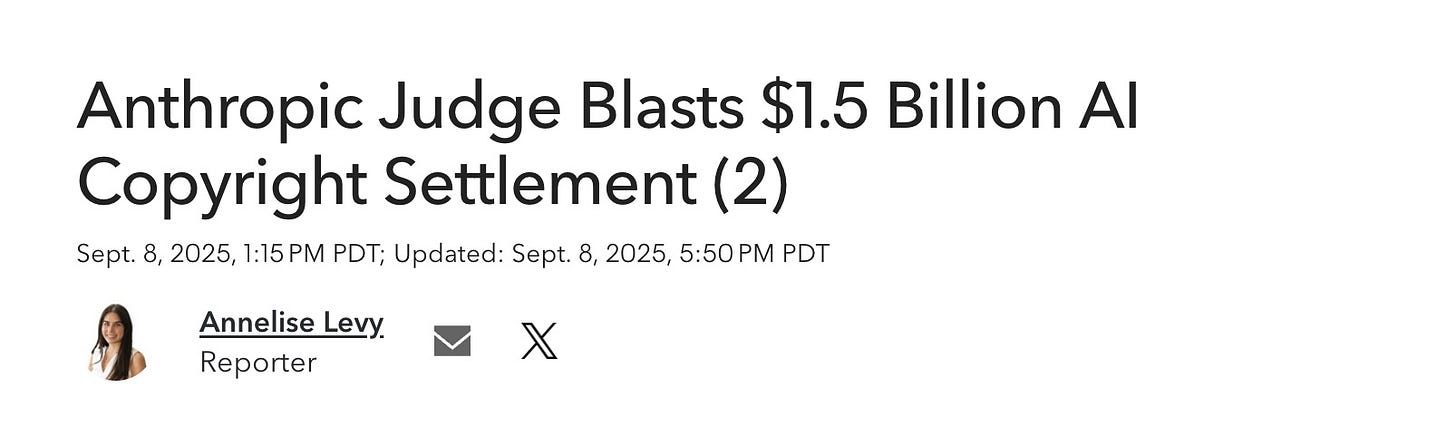

Yesterday morning, this post was mostly done - I was happy with the structure, and was planning on doing a final editing pass or two. And then an errant Bloomberg headline blew it all up (or at least the ending). So I had to spend last night and this morning reworking it. But we'll get to that.

Last Friday, Anthropic reached the largest copyright settlement in US history - $1.5 billion (with a B!) to be split among book authors whose works were allegedly pirated to train their AI systems. The math was straightforward: $3,000 per work, covering roughly 500,000 books the company downloaded from "shadow libraries" without permission.

When I saw the news, my first thought was "Damn, that's a crazy amount of money." But my second thought was: "Hold on - I've published a book. Does Anthropic owe me $3,000?"

Down the rabbit hole

So I did what any reasonable person would do - I started reading legal documents and scouring the internet to find out whether my book was part of Anthropic's ill-gotten dataset.

The AI lab allegedly used two illegal data sources in the suit - LibGen and PiLiMi. Library Genesis (LibGen) and Pirate Library Mirror (PiLiMi) are what researchers politely call a "shadow library." Less politely, they're a massive repository of pirated books, academic papers, and journals that operates in the legal gray area between academic freedom and copyright infringement. If you've ever needed access to a $40 research paper or a textbook that costs $300, you've probably heard of LibGen.

From The Atlantic:

LibGen was created around 2008 by scientists in Russia. As one LibGen administrator has written, the collection exists to serve people in “Africa, India, Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, China, Russia and post-USSR etc., and on a separate note, people who do not belong to academia.” Over the years, the collection has ballooned as contributors piled in more and more pirated work. Initially, most of LibGen was in Russian, but English-language work quickly came to dominate the collection. LibGen has grown so quickly and avoided being shut down by authorities thanks in part to its method of dissemination. Whereas some other libraries are hosted in a single location and require a password to access, LibGen is shared in different versions by different people via peer-to-peer networks.

Back in 2021, Anthropic cofounder Ben Mann allegedly downloaded up to seven million copies of books across the two shadow libraries:

In June 2021, Mann downloaded in this way at least five million copies of books from Library Genesis, or LibGen, which he knew had been pirated. And, in July 2022, Anthropic likewise downloaded at least two million copies of books from the Pirate Library Mirror, or PiLiMi, which Anthropic knew had been pirated.

I'm not entirely sure where the final "500,000 books" came from in the settlement, but my guess is that between duplicates and irrelevant/unusable copies, the majority of the content downloaded didn't end up in the final training data sets. But 500,000 is a lot of books, and I felt good about my chances of being in the data set.

My first stop was The Atlantic's LibGen search tool, which lets you check if your writing appears in LibGen. It's a rough approximation at best - the tool explicitly warns that it's not comprehensive and doesn't cover all the data sources AI companies use. Still, I figured it was worth a shot.

It turned up a hit! But even still, there's no indication whether the book was specifically part of LibGen or PiLiMi at the time of the downloads in 2021/2022. For that, I had to go to the source - LibGen itself.

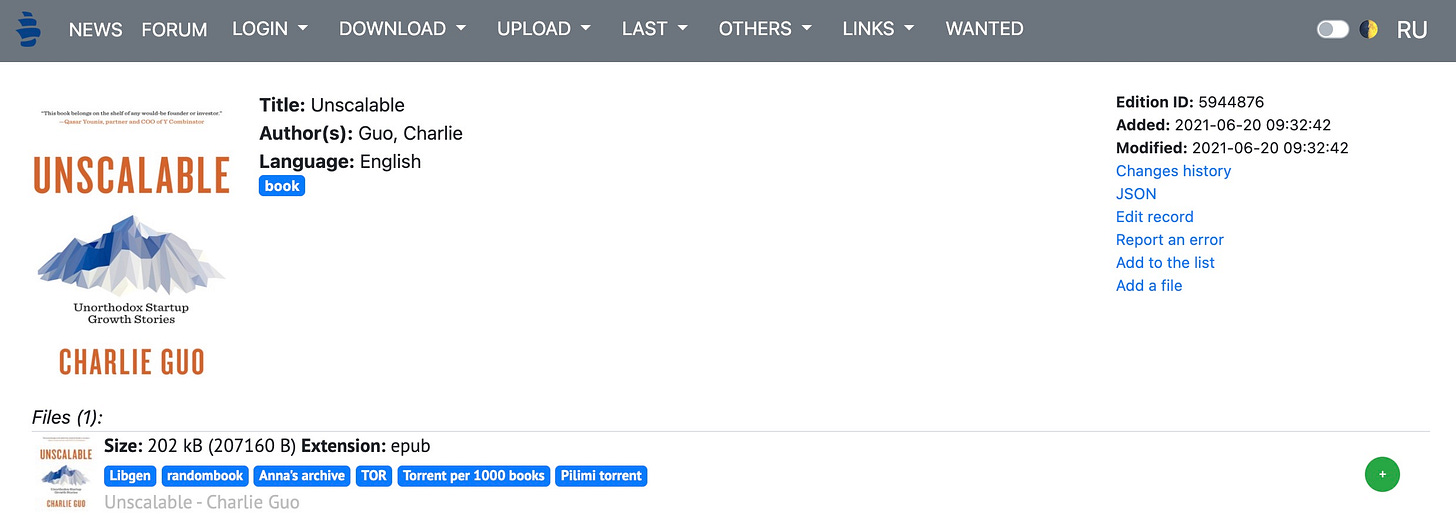

It's still surprisingly easy to access LibGen data these days. Despite a 2015 Elsevier Lawsuit that knocked the main domain offline and a 2024 Pearson Education lawsuit that saw dozens of domains seized, forks and mirrors have proliferated and are available under a dozen or two different domains, if you can find them.

Once I did, a quick search turned up exactly what I was looking for: my name, my book, and an indication that it was added to the LibGen database by June 2021:

Huzzah! Time to sit back, relax, and wait for my check.

Judge Alsup says absolutely not

But here's where yesterday's headline upended my narrative. In the first hearing since the settlement was announced, Judge William Alsup made it clear he was not impressed. The agreement was "nowhere close to complete." He felt "misled" by the attorneys and worried about class members getting "the shaft" once lawyers stopped caring about the details.

This is actually a good thing! The judge has very reasonable points and is trying to help impacted authors1! There was no straightforward claims process for affected authors. No final list of which works were actually covered. No mechanism for handling complex ownership disputes between authors, publishers, and other rights holders. The parties had essentially announced a $1.5 billion deal and figured they'd work out the details later, and the judge (rightly so) said, "I have an uneasy feeling about hangers on with all this money on the table."

However, despite being in my best interests in the long term, the judge's decision leaves me (and my weekly Substack post) in limbo - my potential $3,000 just became much more uncertain. With any luck, I'll have answers sooner rather than later, as the judge gave both parties a September 15 deadline to fix the fundamental problems with their proposal.

Beyond my bank account

The (potential) settlement establishes an important precedent, even if it doesn't set binding legal precedent since it didn't go to trial. The message appears to be: you can train AI on copyrighted material, but you must acquire it legally first.

I found the legal reasoning behind the original settlement fascinating. Judge Alsup's earlier ruling was split down the middle: Anthropic won on the fundamental question of whether you can use copyrighted books to train AI systems. The court found that when books are legally acquired, using them for AI training constitutes "fair use" because it transforms them into something new.

In fact, Anthropic eventually did a lot of this behind the scenes too, hiring the former head of partnerships from Google's decades-old book-scanning project.

Anthropic spent many millions of dollars to purchase millions of print books, often in used condition. Then, its service providers stripped the books from their bindings, cut their pages to size, and scanned the books into digital form — discarding the paper originals. Each print book resulted in a PDF copy containing images of the scanned pages with machine-readable text (including front and back cover scans for softcover books). Anthropic created its own catalog of bibliographic metadata for the books it was acquiring. It acquired copies of millions of books, including of all works at issue for all Authors.

But Anthropic lost on the shadow library issue. The judge found that downloading millions of books from sites like Libgen constituted willful copyright infringement, since the company's executives clearly knew they were using pirated content.

And Anthropic isn't alone in this. Court documents from other cases reveal that Meta employees also used Libgen, with internal comms acknowledging that using LibGen presented a “medium-high legal risk.” During his deposition, Anthropic co-founder Ben Mann admitted he also downloaded Library Genesis data when he worked at OpenAI, assuming it was "fair use."

The use of pirated data sets is the "original sin" of the generative AI industry - Anthropic just happened to be the first to get caught and face consequences. As one intellectual property lawyer put it, "This is the AI industry's Napster moment."

Currently, the legal landscape remains messy, with different courts reaching different conclusions about what constitutes fair use in AI training. For example, the Thomson Reuters v. Ross Intelligence case found that using copyrighted material for AI training was not fair use, though that was for a non-generative AI use case.

But if this settlement finds its way to a successful ending, it may serve as a blueprint for other companies and their IP lawsuits. Even if it's expensive, at least it's a known quantity. The biggest AI labs will know how much to budget for books (or settlements) for future models, even if it is an eye-watering figure2.

Where we go from here

I'm still watching to see what happens ahead of the September 15 deadline. The parties could revise their proposal to address the judge's concerns, but the fundamental problems he identified suggest this won't be a simple process by any means.

But perhaps the weirdest thing about all of this: I still really love Claude!

I'm writing this post in an editor that has Claude integration. I've used it to debug code, brainstorm ideas, and even help structure some of my writing. But now I'm potentially in the strange position of being owed money by a company whose product I rely on. It's like discovering that your favorite restaurant has been using ingredients they stole from your garden - except you still really like the food.

I've talked before about how AI is upending the social contract of the internet, where authors, creators, and bloggers put content out into the world, for free, in the expectation of traffic and views. LLMs are turning that on expectation on its head, as consumers can now get the information without ever visiting the original source. Optimistically, settlements like this could force a better outcome - not just for authors like me, but for establishing clearer rules about how AI companies can acquire training data going forward.

Though at the end of the day, the irony is that I'll probably use whatever I eventually get from this - if anything - to pay for more AI tools.

For what it's worth, I've followed some of Judge Alsup's previous tech-related court cases, including Oracle's copyright lawsuit against Google, in which he learned Java in order to better understand the case. Seems like a thoughtful judge!

Though any big number just means OpenAI, Meta, DeepMind, etc will have more of a moat against smaller startups.