The Industrial Content Revolution

A fundamental change in the structure of the internet.

In the past few weeks, we have seen incredible advancements in text-to-video. RunwayML, Stable Video Diffusion, and now Pika can create remarkably good content. After months of bizarre fever-dream video sequences (remember Will Smith eating spaghetti?) AI-generated videos are having a Midjourney moment.

Even before video, Midjourney itself improved at an astounding pace over the past two years - to quote Andrej Karpathy, we went "from blurry 32x32 texture patches to high-resolution images that are difficult to distinguish from real in roughly a snap of a finger." And if anything, videos seem to be improving even faster than images did.

There's something a little unsettling about this rate of change. I'm not just talking about images and videos - other major trends are building momentum as a direct result of and as a response to AI. It feels like the structure of the internet is being altered in a deep, fundamental way.

And after months of trying to wrap my head around how these changes are related, I finally found a helpful metaphor: the Industrial Revolution.

AI text, images, videos, and voices are becoming dramatically easier to generate and automate. And as a result, we’re entering a new era of digital creation. An Industrial Content Revolution.

Most would agree that the original Industrial Revolution was a good thing - modern life would be impossible without it. So much of what we take for granted - electricity, for example - is a consequence of industrialism. But there were also plenty of downsides: environmental, ecological, and societal.

The same is true of AI content - it will unlock tremendous possibilities that our children and grandchildren will likely take for granted. But in the interim, we need to navigate the profound changes coming for digital content and the internet.

Polluting the world wide web

This week, an SEO consultant inadvertently became Twitter's villain of the day when he bragged about “stealing” SEO from a competitor by flooding their keywords with AI content.

People, understandably, were upset. Many pointed out that Google has become worse at surfacing useful information - many times, the top links are SEO-optimized fluff. A classic example: recipes that explain the author's entire life story before telling you how to make kung pao chicken.

Now, I'm actually a bit sympathetic to the marketer's motivation - as an entrepreneur, you mostly care about finding sales and marketing strategies that work, negative externalities be damned.

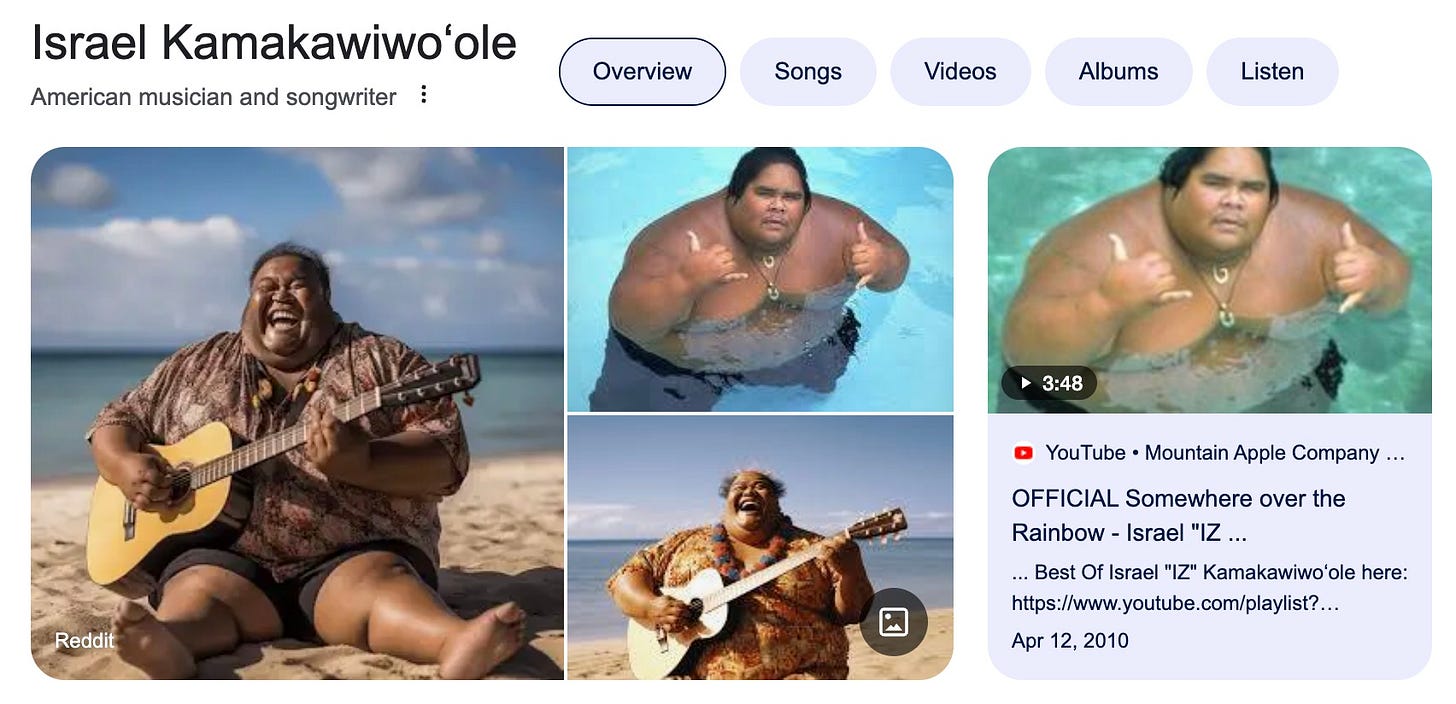

But it’s worth thinking about those second-order effects. Because with AI, we're poised to get even fewer factual results from the web than we do today. Another recent example shows that searching for singer Israel Kamakawiwoʻole results in AI images in two out of three thumbnails:

While generative AI is fantastic from a creative point of view, our systems aren’t designed to handle it from a factual point of view. We’re dumping hallucinated content into the open web, and our search engines cannot currently identify or filter it out. Without better detection systems, we may be unable to trust any digital content moving forward.

Truth is an endangered species

Of course, we've faced this issue before. It's not the first time a new technology has caused a moral panic, and tools like Photoshop have existed for decades.

The argument goes like this: “Even without AI, you can hire a team of overseas writers/editors/artists to create similar content for cheap, albeit not quite as cheap as with AI.”

But this misses a key point: creating SEO spam, while cheap, still took a non-zero amount of effort - hiring good workers, managing their output, reviewing over email or Slack, etc. With AI, we’re not just removing the cost, but the friction. And in doing so, we’re creating problems of scale that can overwhelm our existing infrastructure.

A glaring (modern) example: robocalls. Twenty years ago, telemarketers were obnoxious but manageable. Now, robocalls have made people's phones unusable - at least in the US. Anecdotally, nearly everyone I know refuses to answer unexpected phone calls from unknown numbers - and sometimes those calls are really important!

A more industrial example: overfishing. When fishing with a rod, there’s a limit to the ecological impact that any single person or group can have. But with industrial fishing, massive trawlers and dragnets have threatened species with extinction and fundamentally altered marine ecosystems. As it becomes increasingly challenging for users to find genuine, original content amidst a sea of AI-generated articles, blogs, and images, we risk driving authentic online content extinct.

Some believe that we're at an inflection point in the internet's history - everything that comes after 2023 will be "tainted" with the possibility of being AI-generated. Anyone looking back, whether to check historical data or to train new AI models, will have to grapple with how to deal with AI-generated information.

The tragedy of the digital commons

There’s another key way that the open web is changing. With the explosive popularity of ChatGPT, the world is now aware of the potential of large language models - and the value of datasets used to train them.

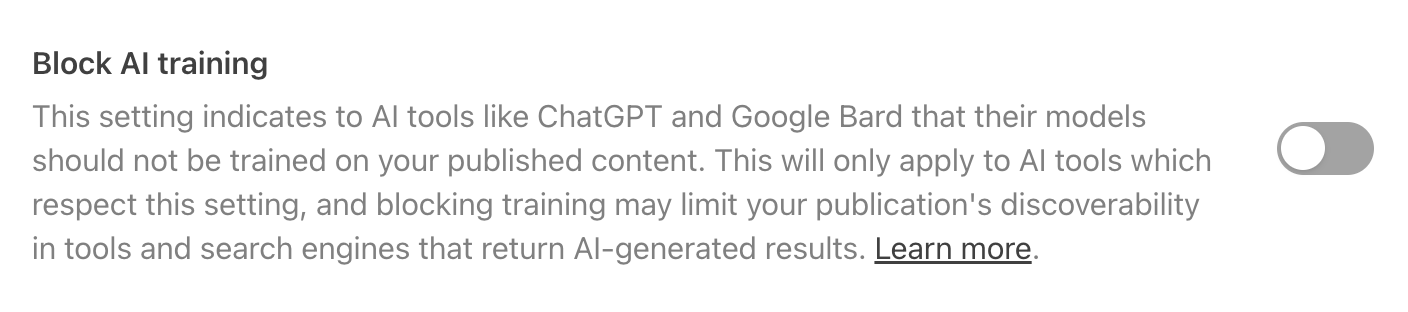

What used to be open pastures of user-generated content are quickly becoming walled gardens. Communities like Reddit and Stack Overflow are now charging to access their content for training purposes - and many new communities are starting on Discord, which has never been publicly searchable. Publications like the New York Times are considering doing the same. Even the platform that I’m currently writing on, Substack, has an option to prevent AI companies from using your work.

This trend started well before AI - social platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn have hidden content from anonymous users and search engines. But there’s a pre-industrial analogy here, too: the Enclosure Movement. The Enclosure Movement took commonly owned land, available for gardening and grazing, and made it privately owned, usually with walls or fences surrounding it.

This might change - multiple lawsuits are arguing that training AI models on publicly available works shouldn’t be allowed at all. Again, I can understand the idea - authors and artists didn’t understand this was a possibility when they hit publish, and now they want to officially change the rules to prevent it.

Without a decisive ruling from the courts, though, we’re stuck in legal limbo. Which means it’s a minor miracle that people are continuing to publicly create and share their work - when an LLM could replicate it in the near future.

However, while publicly available content may be withering, the upsides of automating creativity on a private, personal level are vast.

Engines of creativity

Besides the lawsuits, there is a broader backlash to AI art. Many believe that it dumbs down the craft, has no soul, or is an affront to existing art. I can somewhat rationalize this - with high art, the effort and struggle is often just as important as the output.

But at a practical level - I love this technology. I have approximately zero drawing skills, and can now create almost any image or illustration I want in real time - with a little bit of prompting. I can go even further and turn those images into working software prototypes. That’s an insane amount of productivity!

In a few months or years, I might be able to create entire movies based on what I want to watch. I might have on-demand virtual coaches or experts to talk to, 24/7. I might have truly open-world games that can create endless landscapes and characters. In truth, even I probably don’t appreciate the full extent to which our collective creativity will be amplified in the coming years.

I do get that jobs will be threatened by our ability to automate creativity. I spend my days writing words and code - I’m a prime target for automation here! And I want us to find ways to soften that blow as a society.

But I also appreciate how much automation has improved my quality of life. I wear affordable cotton shirts and wool sweaters, even though they weren’t woven by hand. I walk with rubber shoes on concrete sidewalks past glass window panes, all produced via automation. I don’t want to return to horses, gas lamps, and handmade goods.

As our consumption and creation habits keep evolving, curation will become much more important. As the wave of content grows, finding trusted human curators becomes much more valuable. In particular, human-curated content for news, research, and education is key - at least until we figure out how to get rid of hallucinations.

And even after that point, human creativity is not going away entirely. Despite our advancements in automation, there’s still a role for bespoke goods and services done by humans. Yes, tailored suits and custom furniture are a luxury - but for those who can afford them, they still exist as an option.

Evolving our approach

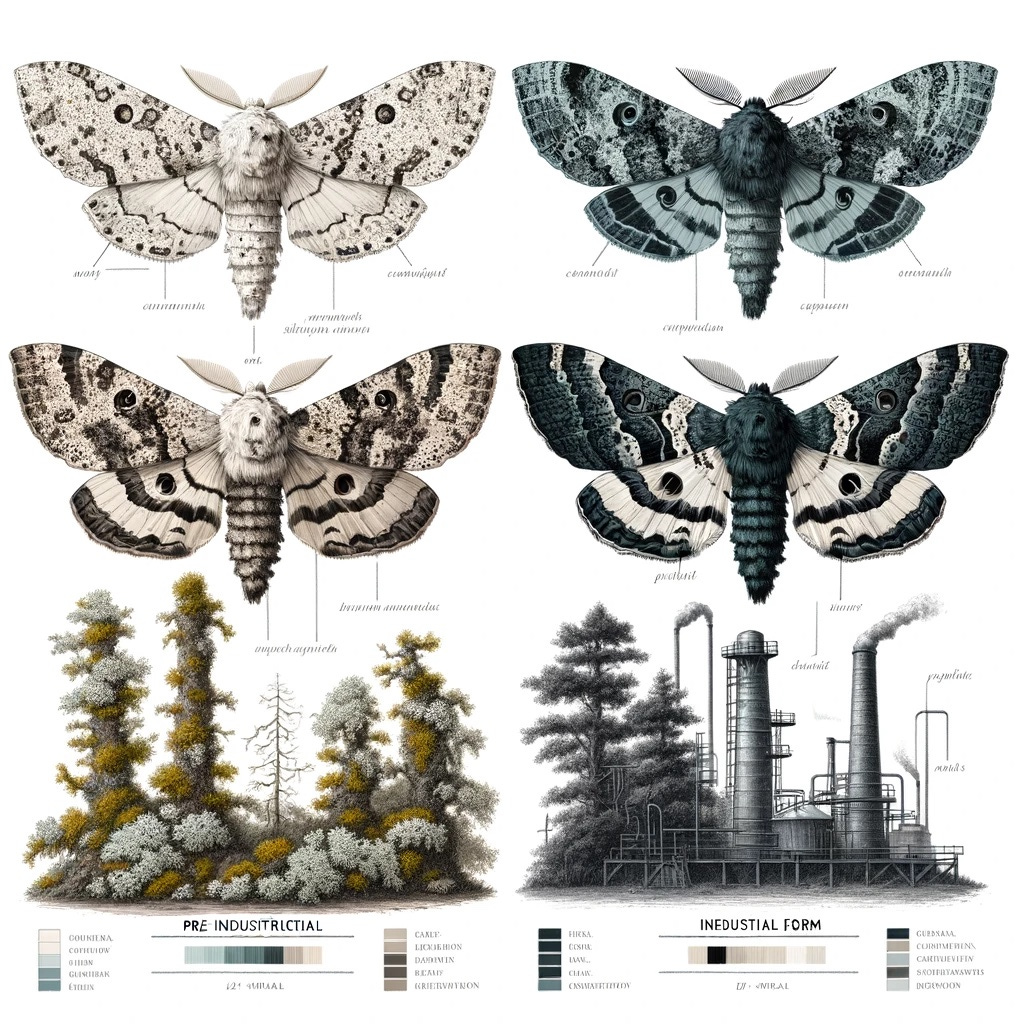

As we entered the 1900s, we realized we could see evidence of humanity’s industrialization in the natural world around us. Geneticists took note of the Peppered Moth, which evolved darker and darker camouflage to match the industrial pollution in its environment.

With our Industrial Content Revolution, our habits, our systems, and even our laws will need to evolve.

I'm not entirely convinced that the tsunami of AI-generated content will "ruin" the internet - if you've previously assumed everything on the internet was 100% true, I have some bad news for you. Yet I believe it will be visible to future generations, much like tree rings can tell us the history of the earth's climate and CO2 levels. Similarly, we may soon find ourselves building new tools to carbon date online content.

It's not as far off as you might think: DeepMind's newest music generation tools come with invisible audio signatures. OpenAI has an internal tool that can identify DALL-E-generated images with 90% accuracy. And beyond the companies themselves, plenty of third-party efforts are underway to help detect AI-generated output (with underwhelming results so far).

But we might also try other approaches: certain artifacts of AI images may come to define historical periods or models, such as malformed hands. We also might have more widespread labeling of AI-generated vs human-generated content. Or, for particularly important or sensitive use cases, we might use immutable, distributed systems to track content creation and modification.

Funnily enough, seeing the world through this lens made me more inclined to support AI regulation. If the past has taught us anything, short-term incentives will win over long-term sustainability. And it took decades of regulation to get better at long-term sustainability: environmental protections, social safety nets, food and drug safety, and labor laws, to name a few.

But with the speed at which AI is moving, we don't have decades. So, while governments may move slowly, start thinking for yourself about how to navigate the changing environment on a personal level. Test out ChatGPT with your workflows as much as you can. Practice spotting AI-generated images against authentic ones (and look at what prompts were used to make said images).

To quote Professor Ethan Mollick: “Faking stuff is trivial. You cannot tell the difference. There are no watermarks, and watermarks can be defeated easily. This genie is not going back in the bottle.”

This is a great summary of what I’ve been feeling about AI, but I dread it’s going to be even more harmful to a lot of people and their jobs. I’m not excited at all. At the individual level, sure it’s fun, but en masse, like you say, it’s different and consequential.

Also, when everyone is a superstar AI enhanced creative, then really nobody is.

This is a great read, thanks for sharing!