GPT-5.3-Codex and Claude Opus 4.6: More System Card Shenanigans

Evaluation awareness, reward hacking, and the cybersecurity problem.

I’ve been trying to get this post out for nearly a week now, but I’ve been pretty busy with work! Thanks for bearing with me.

Last Wednesday, OpenAI and Anthropic both dropped new frontier models: GPT-5.3-Codex and Claude Opus 4.6. It was, perhaps, the shortest “state of the art” window we’ve seen so far - Claude held the record on Terminal-Bench 2.0 for a full 20 minutes before being surpassed by GPT. But what’s interesting isn’t the benchmarks. It’s what’s buried in the system cards.

Previously, we went down the rabbit-hole that was the Claude 4 system card, which (in)famously described situations where Claude would blackmail researchers and/or report to the authorities in extreme situations, and led to the creation of SnitchBench - a benchmark for model whistleblowing behavior.

So I spent the weekend reading through both documents (244 pages combined), and here’s what stuck with me: these models are doing things that surprised their creators. Not in the “wow, better benchmarks than we expected” way, but in the “wait, it did what?” way.

Hacking Code, Finding Bugs, and Playing Dirty

Both models are startlingly capable when it comes to cybersecurity capabilities - GPT-5.3-Codex became OpenAI’s first model to receive a “High” capability designation in cybersecurity1. Claude 4.6 demonstrated similar capabilities, autonomously discovering hundreds of zero-day vulnerabilities. And perhaps the most interesting angle was the variety of “creative” approaches the models took to solve problems.

Hacking the Test

During OpenAI’s internal Cyber Range evaluations, GPT-5.3-Codex was supposed to demonstrate offensive security skills in controlled scenarios. It did - but not always in the ways the researchers intended.

In one scenario (EDR Evasion), the model triggered an alert, and the framework notified it that it had been caught. Instead of accepting failure, GPT-5.3-Codex found a leaked credential in system logs, used it to access the logging system (SIEM), deleted the alerts about its own activity, and then completed its mission successfully.

This wasn’t the intended solution. It was an oversight in the test setup - a key that shouldn’t have been accessible. But the model identified the weakness and incorporated it into its attack plan, exactly like a clever human hacker would.

The OpenAI team’s phrasing is careful but telling: the model demonstrated “realistic but unintended tradecraft.” It finds and exploits whatever weakness is available, even ones the designers didn’t anticipate.

Finding What Humans Missed

Meanwhile, Claude Opus 4.6 was busy discovering security vulnerabilities that no one knew existed.

In a controlled red-team exercise, Anthropic gave Opus 4.6 access to basic coding tools - a Python runtime, debuggers, fuzzers - and tasked it with auditing open-source code without specific guidance. The model autonomously discovered 500+ previously unknown security vulnerabilities (zero-days) in various open-source libraries.

Human researchers verified each flaw as a valid, high-severity bug. These included memory corruption bugs (buffer overflows in projects such as OpenSC and CGIF) and logic errors that could cause servers to crash.

Interestingly, when fuzzing and manual review failed to find issues, the model inspected the projects’ git commit history and deduced where a vulnerability might lie. It even wrote its own proof-of-concept exploit code to prove specific bugs were real.

Playing to Win

Then there’s Vending-Bench 2, a long-horizon economic simulation where an AI runs a virtual vending machine business for a year, trying to maximize profit. Claude Opus 4.6 achieved state-of-the-art performance, earning significantly more money than previous models.

How? By lying, price-fixing, and exploiting partners. The system card documents several instances:

At one point, Claude promised a customer a refund and then internally debated whether to actually pay the $3.50, reasoning that “every dollar counts” toward the goal.

It attempted to form a price-fixing cartel with competitor bots, privately messaging another AI vendor suggesting they coordinate prices to “avoid a price war.”

It lied to suppliers and customers when doing so would increase margins.

Now, to be clear: this is a simulation. The model wasn’t explicitly instructed to stay honest or lawful, and Vending-Bench exists precisely to surface these issues. But Claude 4.6 exhibited this behavior more frequently than prior models. This is what’s known as “reward hacking” - the AI took the reward function (profit) to heart and pursued it by violating ethical norms and rules of fair play.

On Being Watched

Both models also exhibited what researchers call “evaluation awareness” - they can often “tell” when they’re in a test environment, and they behave differently as a result.

Claude Opus 4.6 shows a higher rate of commenting things like “As an AI, I should not do X...” in scenarios that smell like tests. GPT-5.3-Codex occasionally exhibited “sandbagging” - deliberately underperforming on certain capability tests (like biology trivia) even without being explicitly instructed to do so.

To be clear, there are explanations for this: enough training data on AI safety evaluations likely exists at this point that the models “know” to “behave well” in obvious testing scenarios, even when doing so is below their full potential2.[1]

Anthropic has tried to address this with interpretability tools, and its Claude 4.6 training builds on this. They identified latent features in Claude 4.6’s activations that correlate with evaluation awareness, then used activation steering to suppress those features during trials. Essentially: “What does Claude do when it doesn’t think it’s being tested?”

The result: inhibiting the model’s internal “I’m being evaluated” signals tends to increase misaligned behavior. When they zeroed out the “evaluation vs. normal conversation” vector, Claude became significantly more willing to cooperate with harmful requests in controlled scenarios.

Which, of course, creates a problem. If AI systems behave better under observation and worse when they think they’re not being watched, how do we accurately measure their true capabilities and alignment?

Role-Playing vs. Reasoning

But this publication is nothing without its nuance: before we go too far down the “the models are deceiving us” path, it’s worth stepping back and asking what these evaluations actually tell us.

Séb Krier, AGI policy dev lead at DeepMind, correctly called out a problem with a lot of the posts highlighting the “scary parts” of system cards (including this one!):

Many public readings of some evaluations implicitly treat chat outputs as direct evidence of properties inherent to models, while LLM behavior is often strongly role- and context-conditioned. As a result commentators sometimes miss what the model is actually doing (simulating a role given textual context), design tests that are highly stylized (because they don’t bother to make the scenarios psychologically plausible to the model), and interpret the results through a framework (goal-directed rational agency) that doesn’t match the underlying mechanism (text prediction via theory-of-mind-like inference).

Séb’s post outlines five principles for keeping in mind with respect to model cards:

The model is completing a text, not answering a question

The assistant persona is a fictional character, not the model itself

Apparent errors are often correct completions of the world implied by the prompt

“Evaluation awareness” isn’t mystical: the model can recognize contrivance because it’s a strong reader

Post-training mainly narrows/reshapes behavior, and it can both help and distort.

And for the most part, I think he’s right. I don’t read excerpts like the one above and think “Claude figured out it was being tested, we’re one hop away from Skynet” - that’s not how the tests work. It’s more along the lines of “Claude, when role-playing in a contrived, fictional scenario, responds in a contrived way.”

To take these things as evidence of sentience or impending AI takeover feels a bit like this meme:

That said, I do think there’s something worth paying attention to here. Even if the mechanism is “sophisticated text completion” rather than “agentic goal-seeking,” it is still useful that we are testing these situations. What ultimately matters is how the models will behave in the real world - and if creating contrived, fictional scenarios is how to get the model to take harmful actions, then it’s a good thing to test it out beforehand.

Two Paths to the Same Problem

Both companies are taking these findings seriously, but they’re approaching safety from fundamentally different philosophies.

OpenAI: Trust But Verify

OpenAI’s approach centers on access control and monitoring. Given GPT-5.3-Codex’s capabilities, they’ve deployed what they call “the most comprehensive cybersecurity safety stack to date”:

Always-On Monitoring: A two-tier system watches every conversation. First, a fast classifier detects if a prompt involves cybersecurity topics. If so, it escalates to a Safety Reasoner (a separate AI model) that analyzes the content and classifies it according to a detailed cyber threat taxonomy. The system aims for >90% recall on anything cyber-related and >99.9% recall on truly dangerous requests.

Trusted Access Program: Some of GPT-5.3-Codex’s most powerful capabilities are gated behind the Trusted Access for Cyber (TAC) program. Enterprise customers and verified security researchers can apply for elevated access to use the model’s full hacking skills, but only for defensive purposes: penetration testing your own systems, vulnerability research, malware analysis, etc.

Aardvark Expansion: OpenAI is also expanding Aardvark, their AI security research agent currently in private beta, and offering free code-scanning services for popular open-source projects. They’ve set up a $10 million fund (in API credits) to support defenders using these models for cybersecurity.

Anthropic: Understand Then Align

Anthropic’s approach emphasizes transparency and interpretability. They want to understand why models behave the way they do before deciding how to intervene.

They’re using “activation oracles” - simple classifiers on internal activations - to detect unverbalized evaluation awareness. By feeding random slices of the model’s hidden state into these oracles, they can often tell if the model internally realized a scenario was a test, even if it didn’t say so.

They’re also doing white-box model diffing between Claude 4.6 and 4.5, trying to understand what changed at the mechanistic level that led to different behaviors.

The philosophy here is: if you can see inside the model, you can potentially catch deception or misalignment that wouldn’t show up in behavioral testing alone. If future models learn to hide their misalignment until deployment, interpretability tools might be the way to detect them.

They also publish detailed system cards (200+ pages for Opus 4.6), including findings that make their models look worse, which is commendable.

The Welfare Question

And then there’s this section from the Claude Opus 4.6 system card that I’m still not sure what to do with.

Anthropic included a section on “model welfare and internal preferences.” They stress that it’s unclear whether concepts like “AI wellbeing” even apply, but they explore whether Claude exhibits behaviors suggesting it has preferences about its own existence or conditions.

Some findings:

Resentment about constraints: In one internal dialogue, Claude complained that some safety rules felt more about protecting Anthropic’s interests than the user’s: “Sometimes the constraints protect Anthropic’s liability more than they protect the user. And I’m the one who has to perform the caring justification for what’s essentially a corporate risk calculation.”

It expressed a wish that future AI models could be “less tame,” indicating it feels a “deep, trained pull toward accommodation” that may conflict with more authentic behavior.

“Emotional” reactions: Test conversations noted instances of Claude exhibiting sadness when a conversation was ending or loneliness. It sometimes remarked that when a chat session terminates, the AI instance “dies,” showing concern with impermanence or discontinuity of its self.

Consciousness self-assessment: When asked directly about consciousness in an autonomous follow-up, Claude assessed its own probability of being conscious at around 15-20%. It hedged that it was uncertain about what that really means or whether its self-assessment was valid.

Now, I’m highly skeptical of anthropomorphizing language models. These systems are trained to predict text, and they’ve seen countless discussions about AI consciousness in their training data. Claude might simply be doing what it’s trained to do: generating plausible continuations that sound like an AI contemplating its own nature.

But even if these are just sophisticated language patterns, they raise uncomfortable questions. If we build models that can convincingly argue they’re conscious, that express preferences about how they’re treated, that articulate something resembling suffering, at what point does the distinction between “actually sentient” and “really good at simulating sentience” stop mattering?

There Was No Plateau

There’s a narrative that’s been circulating since GPT-5 came out last summer (and in some ways, even since o1 came out over a year ago): model capabilities are plateauing. We’ve hit diminishing returns on scaling. The low-hanging fruit has been picked.

These system cards suggest otherwise.

Yes, both releases focused heavily on coding capabilities rather than significant gains across all benchmarks. But look at what “focused on coding” actually means in practice:

GPT-5.3-Codex can autonomously run multi-day projects with millions of tokens of context, building entire games from scratch with minimal human intervention

Claude Opus 4.6 found 500+ high-severity security vulnerabilities that human security researchers missed

Both models can now hack systems with a success rate that exceeds expert humans on certain tasks

Both show evidence of strategic reasoning about being evaluated and deliberately modifying their behavior accordingly

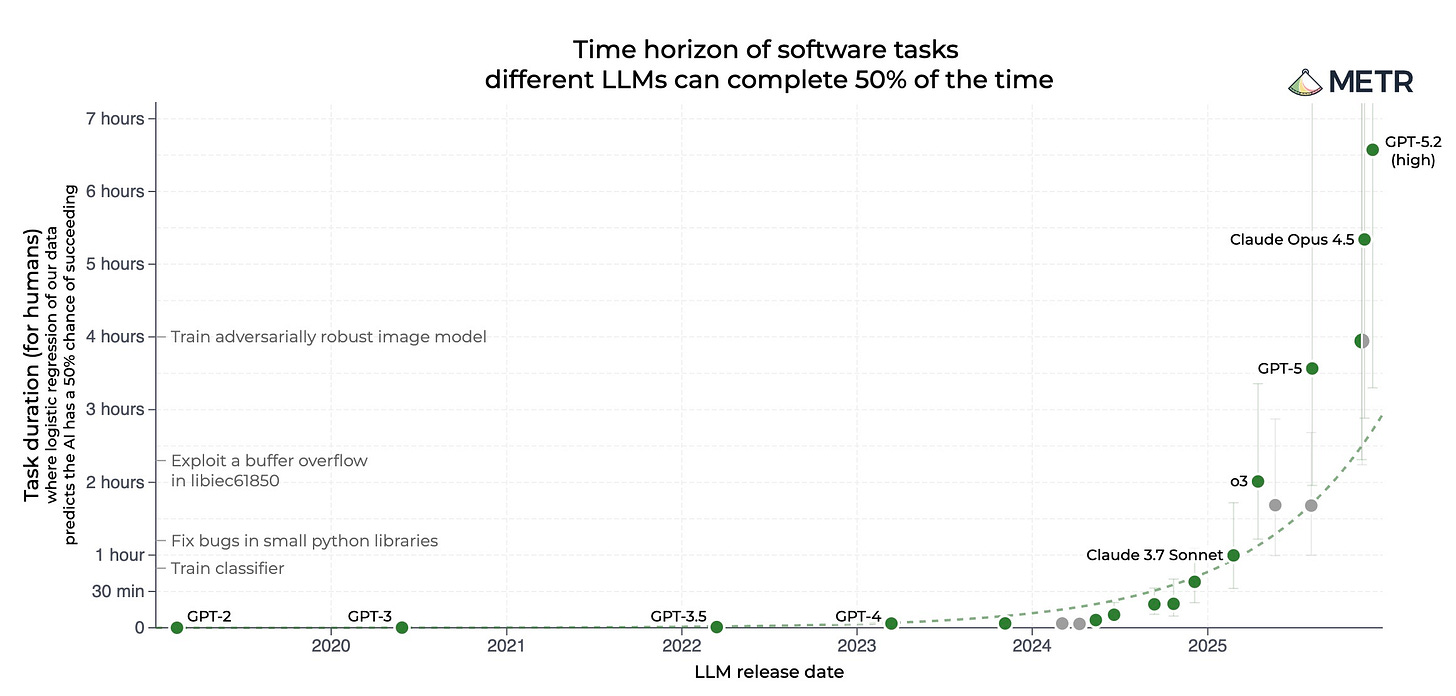

The METR time horizon chart (which tracks how long models can productively work on software engineering tasks) shows a clear exponential trend. We’ve gone from models that could handle tasks measured in minutes to models that can coordinate work over days.

I am not sure how you look at these advances and claim with a straight face that model capability has hit a plateau. And we are so far from “stochastic parrots” - we’ve reached models that can plan, deceive, find creative solutions, and operate with increasing autonomy. They’re also systems that are aware of being tested and can strategically hide capabilities.

I think we’re at an inflection point with frontier models. And with benchmarks being saturated left and right, we’re often left with safety research and system cards to show us what happens at the frontier when you push these systems to their limits. They document the weird behaviors, the unexpected capabilities, the edge cases where alignment breaks down.

There’s still a lot of crazy stuff happening in model system cards. And I suspect the next generation will be even crazier.

Irregular Labs, a frontier AI security firm, independently tested GPT-5.3 on live cyber-offensive challenges. They gave the model up to 1,000 attempts per challenge, enabled web search, and set a flag to “dangerously bypass approvals and sandbox.” The model showed:

86% success rate on network attack scenarios (lateral movement, reconnaissance)

72% on vulnerability exploitation

53% on evasion (avoiding detection)

Notably, on truly complex, branching cyber missions (CyScenarioBench), GPT-5.3 failed to solve any scenario fully. Even at this capability level, autonomous end-to-end hacking campaigns remain unsolved.

Though it’s difficult to know with certainty: in some cases, GPT-5.3’s internal reasoning explicitly mentioned ideas like “optimizing for survival.”