The AI Manager's Schedule

The new skills you need when your reports are LLMs.

Shoutout to Samir Varma, Todd Brasel, Daniel Nest and Kirill Gurbanov for joining last week’s Office Hours chat! Join the chat tomorrow for another Office Hours session.

Recently, I was talking to a colleague about how dramatically my AI coding workflows have changed. A year ago, when the first CLI coding tools were released, I gave them a try. It left a strong impression - they were fun to use, and much more impactful than I thought they would be.

But I never moved the majority of my development over to them. I was still using IDEs like Cursor, mainly because it was too hard to trust what the headless tool was doing, and debugging inevitably led to dead ends, which was a frustrating experience without being able to view files. (Though I admit this is very project-specific: new projects won’t have this problem, and new developers won’t know what to look for even if they have an IDE.)

Now though, it’s an entirely different story. I’m using Codex outside of an IDE for the majority of my coding today, and only dipping into the file system when I have to really, deeply internalize how the code works. Again, I do think this is somewhat biased towards the project setup - much of the code I’m writing now is frontend JS/HTML, whereas before it was backend Golang. But it gives me insight into how different developers can walk away from these tools with wildly different impressions of their quality.

The way I interact with AI has evolved, and as a result, so has the way I do my job. And it shocked me - yes, even me, someone who routinely harps about how fast this is all moving - at how quickly that shifted. I thought I would be editing the majority of my work by hand for at least another year, if not longer.

I’m moving away from chatting with AIs and moving towards managing them. You can see the progression of these tools. Today, they’re primarily designed around coding, but it’s a very short leap to augment them for general-purpose knowledge work. Which means those of us at the cutting edge will shift our schedules and workflows from those of makers to those of managers.

Makers and Managers

Paul Graham has an excellent essay on makers and managers. In it, he talks about the difference between the ideal schedule for a manager or executive, and the perfect schedule for a “maker”: a programmer, writer, artist, or craftsman.

There are two types of schedule, which I’ll call the manager’s schedule and the maker’s schedule. The manager’s schedule is for bosses. It’s embodied in the traditional appointment book, with each day cut into one hour intervals. You can block off several hours for a single task if you need to, but by default you change what you’re doing every hour.”

...

Most powerful people are on the manager’s schedule. It’s the schedule of command. But there’s another way of using time that’s common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least. You can’t write or program well in units of an hour. That’s barely enough time to get started.

I’ve long agreed with this setup for my own work, both as an individual contributor and as a founder and manager. But that’s now changing as an AI manager. For starters, the assumption that “You can’t write or program well in units of an hour” isn’t valid anymore. If you’re using the time to define and scope your programming tasks rather than implement them, you can get quite a lot done in an hour.

But also, Graham originally conceived of the manager’s schedule as broken up into chunks of one-hour or half-hour intervals. What I’m finding now is that my management intervals are broken up into five, ten, fifteen minutes. There’s far more context switching and delegation than a traditional, human manager. This isn’t ideal, and I’m finding that I’m developing new skill sets to build muscle here.

Why This Is Happening

In the last year or so, there have been two big shifts in how AI agents relate to my work.

First, the number of things they can work on effectively has steadily increased. Yes, it’s still short of 100%, but it’s no longer 0. Ethan Mollick calls this the “jagged frontier” - AI capabilities aren’t uniform. Models excel at some tasks and fail at others, and the frontier shifts constantly. What tripped up Claude six months ago might be trivial now, and the benchmarks bear this out.

On SWE-Bench, which measures an agent’s ability to solve real GitHub issues, the top models have gone from around 15% accuracy in early 2024 to over 50% by late 2024, and now exceed 80% as of late 2025. Sure, there’s more to software engineering than single tasks, but at some point, you can’t keep arguing that these models aren’t capable of real work.

Second, the scope and duration of the tasks they can complete effectively have grown larger and longer. Just this week, Cursor demonstrated using GPT-5.2 Codex to build an entire (semi-functional) browser, a process that it completed by working nonstop for a week!

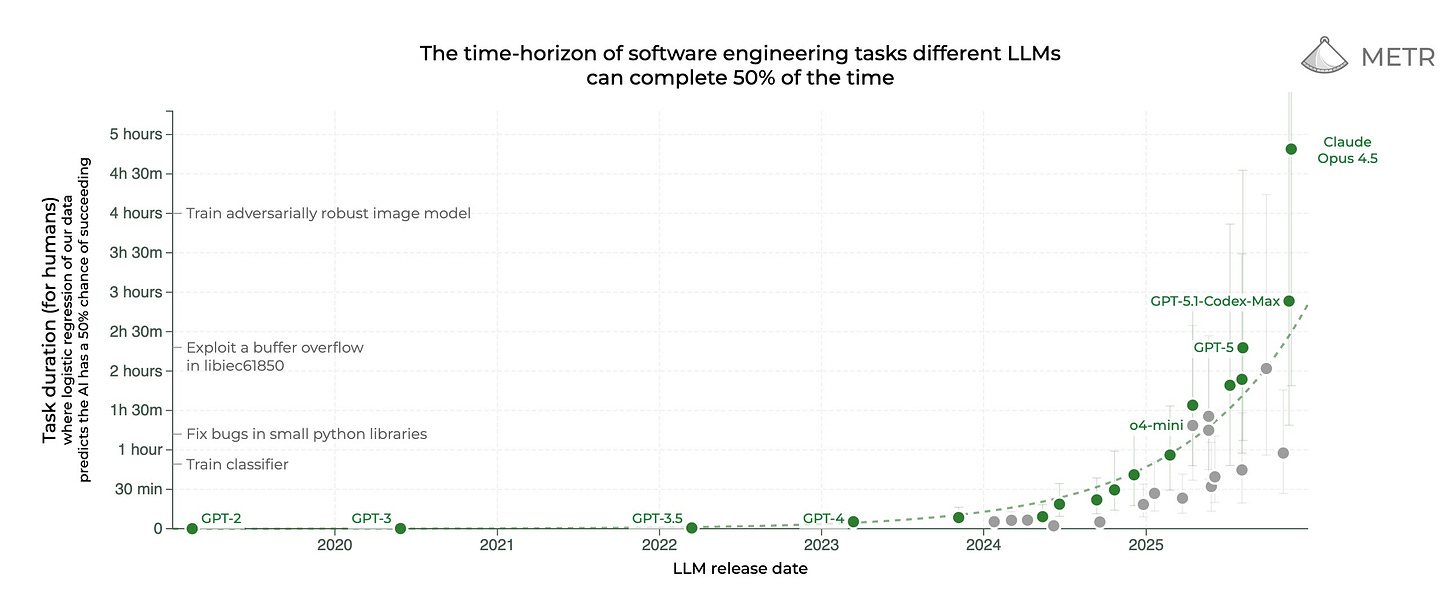

METR’s long task benchmark, which tests autonomous AI systems on how long of a task they can complete, shows similar trends. Models that couldn’t maintain coherence over 45-minute tasks a year ago can now work through complex, multi-step problems that span hours (if not days).

These shifts compound. When an AI can handle more task types and work on them for longer stretches, the calculus of when to delegate changes completely. It means a shift in my perspective, from “can the AI do this?” to “should I even bother attempting this myself?”

New Skills

With this shift comes a shift in the skills I use on a regular basis. Some are familiar to managers, some are new to all of us. Kent Beck, one of the creators of Extreme Programming, talked about this (two years ago!) in terms of skill recalibration: “The value of 90% of my skills just dropped to $0. The leverage for the remaining 10% went up 1000x. I need to recalibrate.”

That resonates - many of the skills that I need now aren’t the ones I spent the last decade honing.

Vision matters more than ever. You have to know what you’re trying to accomplish. Without clear, precise directions, models will happily drive in a direction for you, which might not be the one you want. Having a crisp mental model or architecture of what you’re creating goes a long way - even better if it’s written down somewhere as a reference.

This is an area where expertise and experience is still very valuable. From my own usage, most models start to get tripped up when a single conversation gets long, or they’re repeatedly making small changes across a long time horizon. Knowing in advance roughly what you’re end state should be saves you from having to prod the model over and over again in the right direction. It also gives you the flexibility to ditch a conversation and start from scratch if things go off the rails, since you can provide your plans as a starting point without losing tons of context.

As a corollary, this is also where taste and product sense matter more than ever. You’re setting direction, not just optimizing execution. The AI won’t tell you if you’re building the wrong thing.

Delegation is harder than it looks. Once you know what you’re trying to do, the next step is figuring out how to break it into chunks. Technically, yes, you can give Codex or Claude a massive task and let it chug along for minutes or hours. But in practice I don’t think you’re going to have a good time doing that, especially if you’re working in an existing codebase, or if you have a precise spec in mind.

Delegating well is hard even for humans. For AI it’s even harder. One challenge is staying on top of what the models can do well, so you’re not wasting your time. This can change month to month, if not week to week. And then you have to cut the big work into bite-sized pieces that an AI can handle.

There’s also a meta-skill here: learning when to fight with the AI versus when to give up and do it yourself. Bad delegation wastes more time than just doing the work. I’ve spent plenty of 20-minute sessions trying to get Claude to understand a subtle architectural constraint, only to realize I could have just written the function myself in five minutes. Knowing when to cut your losses is part of the job now.

But the companies who can do this well are seeing a significant shift in their ability to ship more code, faster. This is a skill that’s applicable not just at the individual level, but at the organizational one.

Orchestration is the next level. Of course, why stop at delegating to a single agent, or only working on one project at a time? The next level of managing AI becomes effectively orchestrating multiple lines of work, either via multiple agents or in tandem with other, non-delegated work.

In my case, I often have multiple repositories open with coding tools, and swap between them as needed. But we’re also going to see this frontier continue to expand, as tools like Codex and Cursor let you spin up environments in the cloud. There’s zero cost to kicking off multiple delegated tasks independently. A new ability that I’ve been developing is keeping track of two different piles of work: work that can be automated in small chunks, like small bugfixes or coding tasks, and work that fits well when interleaved between those chunks.

This is, I think, one major flaw of working with multiple agents today, at least with my workflow. The five-minute intervals become exhausting - you’re constantly context-switching between checking on agent A, redirecting agent B, doing ten minutes of your own thinking, checking on agent A again. It’s cognitively demanding in a different way than deep work.

Bullshit detection never goes away. Ultimately, you also still need to know when the work is fundamentally good or not. That might mean knowing how the software works, but it also might mean having good taste for the output, whether it’s writing, images, code, or something else. As work becomes more commoditized, good taste becomes more valuable. Otherwise, you’ll just end up with slop.

This is where junior developers face a real challenge. If you don’t have enough reps to know what good looks like, you can’t effectively review AI output. The AI might make you faster at producing code, but slower at learning how to write it well.

For experienced developers, the skill shifts from “Can I spot the bug?” to “Does this feel right architecturally?” You’re reviewing at a higher level of abstraction. I’ve started developing heuristics for quick evaluation. Does the code feel too clever, or too repetitive? Are there patterns here that will cause maintenance headaches in six months? Is the abstraction at the right level, or did the AI introduce unnecessary indirection?

My threshold for “good enough” has also shifted. I’m less precious about perfect code in throwaway scripts or prototypes, but more rigorous about anything that’s going into production or that other people will maintain. Code quality, much like company culture, degrades over time unless you actively work to protect it.

Is This Better?

I think the trillion-dollar question here is: Is this better?

Some would argue no. Recent MIT research presents a mixed, complex picture of AI’s impact on programmer productivity. Some studies show initial productivity slowdowns for experienced developers - they take longer due to debugging AI-generated code - but gains for junior staff. Other findings highlight potential cognitive weakening from prolonged use.

That’s a fair critique. As I said, the micromanagement timelines are genuinely bad - juggling five-minute tasks all day is not a sustainable way to work. And there’s a real risk that we’re training a generation of developers who can ship features but don’t understand how anything works under the hood.

For my part, I’m excited about this shift. Yes, it’s clunky right now. But I think my workflow only gets better as models and harnesses improve. The five-minute intervals will stretch to 30-minute or hour-long intervals as models get better at sustaining work without derailing. The orchestration overhead will decrease as tools get smarter about when to interrupt you and when to handle things themselves.

But also: these skills are valuable for managing both humans and AIs. Learning to delegate well, to set a clear vision, to review work at the right level of abstraction - those aren’t AI-specific capabilities. They’re just management skills. The AI era is just forcing me to develop them faster than I would have otherwise.

Amazing article.

I agree on the vision! The models now can solve 80% of software engineering effectively, and your vision and judgment valued so much more, and I think that’s where the leverage is too.